Activist, Academic, Ambassador: Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja ’67 Named to UN Post

March 9, 2022

- Author

- Mary Elizabeth DeAngelis

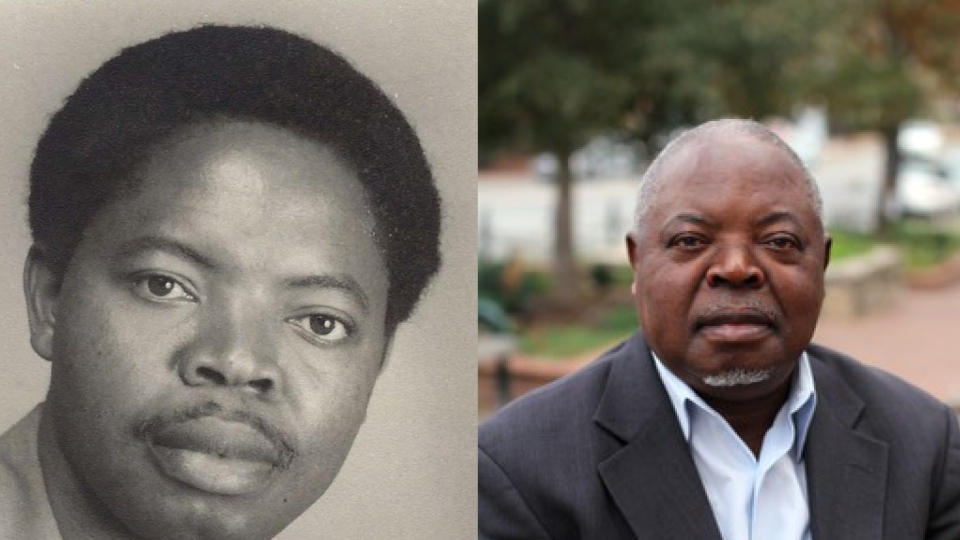

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja ’67

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja grew up in the Belgian Congo with a strong sense of racial clarity.

White people enjoyed modern homes with electricity and streetlights. Black people lived across town in thatched roof houses lit by kerosene lamps, their streets dark at night.

Black residents, from housekeepers to nurses to schoolteachers to carpenters and tailors like his father worked for the white missionaries in the American Presbyterian Congo Mission station of Kasha. Young Black and white children often played together. That stopped as they got older, and some white teenagers used racial slurs to belittle their former playmates.

Racial discrimination existed everywhere. Black people had to wait in long separate lines to buy a train ticket, while white people could purchase one instantly. White police beat Black prisoners in the public square.

Nzongola-Ntalaja’s activism got him expelled from high school, when as a teenager he joined protests supporting Congolese independence from Belgium. It continued at Davidson College, where he became immersed in America’s civil rights movement, and expanded during his decades as a scholar.

Some 60 years after leaving his country for the first time, Nzongola-Ntalaja ’67 serves as the new United Nations ambassador and permanent representative for the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Africa’s second largest country is rich in natural resources, but struggles with high poverty, violence and instability.

Nzongola-Ntalaja wants to draw international attention to its needs—and great promise.

The ambassador has many obligations in these tumultuous times. Last week, his country joined the majority of United Nations members voting to demand that Russia stop its invasion of Ukraine. It’s a non-binding resolution intended to further isolate Russia and reinforce that the world opposes the assault.

There are parallels here. Russia’s fight to claim sovereignty over Ukraine rings familiar to this son and scholar of Africa.

“The DRC has greatly suffered from external sponsoring of secessions and from occupation, human rights violations and the plundering of our abundant natural resources by neighboring countries in the East,” Nzongola-Ntalaja said. “We would like to see all countries in the world, and not only Russia, respect the UN Charter and international human rights and humanitarian laws.”

Davidson Activist

Nzongola-Ntalaja holds a prominent place in Davidson’s history.

As the civil rights movement swept through the United States in the early 1960s, some students and faculty members urged Davidson leaders to admit Black students. Nzongola-Ntalaja was an exchange student in Montana with plans to attend Macalester College when Davidson President Grier Martin called his host family’s home. Martin offered him a full, four-year scholarship.

Nzongola-Ntalaja’s activism got him expelled from high school. . . It continued at Davidson College, where he became immersed in America’s civil rights movement, and expanded during his decades as a scholar.

He became the second Black student to attend Davidson during its early efforts to diversify. And he quickly assimilated into American activism. He joined civil rights protests in Charlotte, urged the college to stop discriminating against Black employees, and advocated for a broader curriculum.

Black and white maintenance workers at the college had similar jobs but received different treatment. White workers, classified as maintenance engineers, got paid more than Black workers classified as janitors. He’d seen that dynamic in the Congo, where whites doing the same jobs as Black workers earned vastly bigger paychecks.

It shocked him.

“Here I was in America—the land of liberty, equality and justice,” he said. “And in reality, that wasn’t the case. I went to President Martin and told him that this was ridiculous and revolting and needed to stop.”

Martin agreed and said things would change. Not quickly enough: The college lost outstanding Black workers to other employers that offered better pay and treatment, Nzongola-Ntalaja said.

The budding scholar also found Davidson severely lacking in African studies.

He asked college leaders to expand course options to include Africa and the African Diaspora in the Americas. Davidson needed “to recognize that true diversity requires going beyond the physical presence of a handful of students of African ancestry…to recognize the intellectual and cultural productions of their peoples as worthy of being integrated into the curriculum.

“I am happy to report that this message was effectively heard,” he said.

Professors asked for his help and reading recommendations as they designed an African studies course together.

Ken Childs ’66-67, his white classmate and former roommate, remembers marching with him to support the Civil Rights Act of 1964. They both went to hear Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speak at Johnson C. Smith University, a historically Black college in Charlotte.

“Georges was very outgoing and personable and obviously very invested in the civil rights movement,” Childs said. “He was also incredibly involved in African affairs, and a leader among Congolese students in the United States.”

Not all welcomed his presence.

Nzongola-Ntalaja and Benoit Nzengu ’66, the first Black student to attend Davidson, faced resentment and prejudice from some white students and professors who didn’t think they belonged at the college.

Both played soccer and would encounter restaurants that refused to serve them. Their coach wouldn’t stand for that and threatened to pull the whole team from the restaurant if the two Black students weren’t served.

Childs remembers a Mooresville restaurant that wouldn’t let Nzengu eat there.

“They told us they did not serve Black students,” Childs said. “We all got up and left, we were so embarrassed and disgusted.”

Both Nzengu and Nzongola-Ntalaja have described the college as more accepting than many places.

“At that time of segregation, Davidson was something like a pioneer in its willful hope for better days,” Nzengu said during a 2012 speech at the college. “Moreover, in its fight for greater justice for all, the college was a beacon of courage and determination, and above all, love for all human beings.”

The two Congolese students set the stage for the college’s first Black American students, Leslie Brown and Wayne Crumwell, who came to Davidson in 1964.

Outspoken Critic of Authoritarianism

Nzongola-Ntalaja originally envisioned a medical career. But as he became more involved in the civil rights movement, he switched from a pre-med track to a philosophy major.

After Davidson, he received his master’s degree in diplomacy and international commerce from the University of Kentucky, and a doctorate in political science from The University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 1971 he returned to Africa and taught for nearly three years, the first at the Congo Free University, (then a Protestant university, now the University of Kisangani) and the last two at the National University of Zaire’s Lubumbashi campus (now the University of Lubumbashi.)

His country’s democratic gains of the early 1960s had succumbed to General Mobutu Sese Seko’s takeover in a 1965 military coup. Mobutu renamed the country Zaire.

Nzongola-Ntalaja’s vocal criticisms of Mobutu’s authoritarian, violent and corrupt regime subjected him to harassment and death threats. The Security Police interrogated him for hours. He returned to the United States and remained in self-imposed exile for 17 years.

He taught African Studies at Howard University and published numerous articles and several books about his home country. He returned to Davidson as a visiting political science professor in 1990, then nine years later as the James K. Batten Professor of Public Policy.

In 1991, he returned to the Congo, joining the Congolese Sovereign National Conference the next year. Their main objective was to get Mobutu out of power and create a democracy. That didn’t happen until Mobutu was overthrown in 1997 and forced into exile. The country went back to its original name—and continues working toward a stable democracy.

Nzongola-Ntalaja has been a professor specializing in African and global studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) since 2007. His primary affiliation is with the Department of African, African American and Diaspora Studies. He’s also held a joint position as a global studies professor since 2013. He has served in various DRC governmental and United Nations advisory roles.

He’s a past president of the African Studies Association of the United States and of the African Association of Political Science.

New Role, New Possibilities

DRC President Felix Tshisekedi tapped him to be the country’s UN ambassador in October and he presented his credentials in January after finishing the fall semester at UNC-CH. He’s taken a leave of absence from teaching and lives in New York with his wife, Jeanne Kulondi Lupumba-Nzongola.

That offers him a chance to work with some of the world’s most influential leaders as he pushes for economic opportunities, environmental protection, peace and stability in a country harmed by centuries of mistreatment and exploitation.

“Our diplomacy has failed to show the best image of our country. We have a lot of problems. We’re at war in the eastern Congo. Many of the people responsible for the 1994 genocide in Rwanda have settled in the Congo,” he said. “We have militia groups responsible for the rapes of women. There’s anarchy and suffering, and the international community doesn’t pay much attention to it.”

And yet the country is rich in forests, valuable minerals such as cobalt and lithium, and in a prime position to be a green energy leader. He says he’ll use his platform to promote and protect its potential.

“It’s a wonderful and useful opportunity to defend the interests of my country in the international community,” he said. “We have a lot to offer the world. We need the world to help us provide stability.

“There’s a lot of work to be done.”