Beneath the Grit and Grime: Painting Conservation Pioneer Ginny Newell ’78

October 4, 2023

- Author

- Caroline Roy '20

Ginny Newell ’78 at work in the main room of her studio.

“To whom much is given, much is required (Luke 12:48)."

Ginny Newell ’78 attached this Bible verse to her bathroom mirror when she first moved to Columbia, South Carolina, to work in an art gallery. She would eventually open her own art conservation lab, ReNewell, Inc. Fine Art Conservation, in 1983. The phrase has guided her through 40-plus years of conservation work, and assumes a new meaning as she prepares to retire.

Today, every room of Newell’s studio is packed with work and memories accumulated over the years — paintings at various stages of restoration, ornate frames halfway scrubbed of grime, a personal timeline of photos tacked to a large bulletin board in her office and reminders scrawled on index cards and sticky notes.

If it is difficult, we do it immediately. If it is impossible, it takes a little longer. Miracles by appointment only, reads a note just inside the front door.

Pioneering Paper Conservation

Newell is one of the few conservators in the Southeast who specializes in restoring fine art on paper, a skill that requires years of intensive scientific training and careful attention to the paper’s internal structure. She received her professional training at the Academy of Professional Arts and Science in Sonoma, California, working one-on-one with a master conservator, and later studied conservation in Amsterdam.

“After years of treating only oil paintings, I realized there was a huge need for paper conservation,” she said. “In the Southeast, humidity, mold and foxing present issues that my colleagues out West have little experience with, so I offered both painting and paper conservation. That’s the niche I’ve created, and that’s how I’ve been successful.”

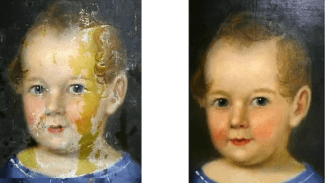

Detail of William Garl Browne (1823-1894). “Self Portrait as Child.” Newell removed oxidized varnish and overpaint.

She relied on word of mouth to grow her business, handling each piece with painstaking care and letting the quality of the work speak for itself. Soon, she found herself working with clients from New York to Florida.

Restoring a single painting can take weeks, if not months, so Newell works on several at a time. When a painting comes to the studio, she first writes a condition report chronicling the damage and then a treatment proposal. When the client agrees to the proposal and estimate, she gets to work removing surface grime and old varnish, lining the painting, or, as with paper, targeting the degraded or stained areas and then mending any tears with tissue. It’s a delicate process, and every step must be handled with the utmost care. Always, Newell adheres to conservation’s two most important rules — do no harm, and make it reversible.

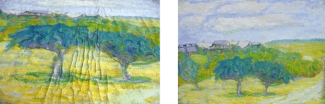

“The Path” by Caroline Guignard, Oil on canvas. The painting suffered from tenting, lifting and cupping caused by exposure to excessive heat and moisture.

“When I clean a painting, I still get a thrill,” she said. “It could be the gazillionth painting I've done, and it's still amazing to me that I can lift years of grime and oxidized varnish without disturbing the paint layer. I am blessed and amazed that my career and passion has been one that combined my interests in art and chemistry.”

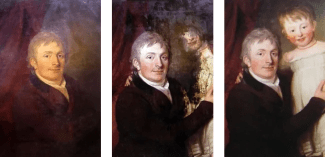

Among her current projects are original watercolors by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, but a recent portrait of a client’s unknown ancestor presented a fascinating surprise. As she cleaned the background, a shape began to emerge from the grime. At first, she worried she had burned through the paint layer, but slowly, tiny fingers emerged. She kept cleaning to reveal a child — completely hidden behind layers of paint — standing beside the original subject.

Restoration of "Mr. Nicholas Salisbury, a Liverpool Merchant" by J. Allen revealed a child who had been intentionally painted over.

Even as Newell prepares to step away from her work, discoveries like this one keep her love for conservation alive.

“It’s kind of like golf,” she said. “You can have a horrible round, but you hit one good shot and that keeps you coming back. I can have weeks of problems and headaches and gnashing of teeth, and then I’ll have one perfect moment that makes it all worthwhile.”

Stepping Down

When Newell opened her studio in 1983, she was the only conservator in the area. She worked alone and with various assistants for 16 years before hiring Jeff Donovan, whom she trained in inpainting, a process of filling and toning areas of lost paint without covering the original paint. Three decades later, Donovan still handles the meticulous work of inpainting the lost areas of each piece.

In 1998, she helped found the Southeast Regional Conservation Association (SERCA), a non-profit organization intended to promote collegiality and raise general awareness of art conservation. The group holds an annual meeting and occasional workshops for conservators to refresh their skills. As new technologies and methods emerge, the science of conservation is always evolving.

“I told myself early on in my career that I would keep going as long as I was learning new things,” Newell said.

While the decision is bittersweet, she feels ready to step away from the studio after years of difficult, yet rewarding work. Before she can step down, she must finish the projects on her plate, sell her specialized equipment and chemicals to the next generation of conservators and move out of the building she’s called a second home for 40 years.

After closing on her new home in Davidson and making plans to move this summer, Newell is feeling excitement about beginning a new chapter in life.

“I was afraid that, despite my wonderful friends in Columbia, I would isolate myself once I lost the stimulation of my career,” she said. “I wanted to be in a place where I could walk to campus and hear lectures or go to music or arts events. I want to live where there is love, and there's a lot of love in Davidson.”

Giving Back and Going Home

Newell’s relationship to Davidson goes back to the beginning of her life. She grew up visiting campus with her father, C. Morris Newell ’49, who played golf as a student and remained highly involved with his alma mater throughout his life.

Davidson was her first choice, but she struggled to find community during her years as a student. It was 1974, and while Davidson had officially admitted women students the year prior, only about 70 women lived on campus. Most lived together in the women’s dorm, but Newell and her roommate were instead placed in President Sam Spencer’s garage apartment, isolated from the rest of the group.

In hindsight, Newell said her loneliness drove her to invest more time in art. She’d originally planned to become a doctor but fell in love with art history after hearing a humanities lecture by Professor Larry Ligo.

“He taught me that paintings can be read,” she said, “and then he taught me how to read them.”

She occupied herself by creating a small gallery in the college union, accepting various internships at the Mint Museum in Charlotte, developing her photographs in the darkroom, and “escaping” for a semester to study art history in France on Ligo's first study abroad trip.

To her surprise and delight, some of her strongest connections to Davidson developed after graduation, when a group of women in her class invited her on a girls’ trip to the mountains. They’ve remained friends ever since.

As her ties to Davidson progressed, so did her career, but Newell always returned to the words on her bathroom mirror — to whom much is given, much is required.

Among her contributions to campus are the C. Morris Newell Golf Scholarship in honor of her father, whom she describes as “a force of nature,” the Virginia E. Newell ’78 Scholarship and the Ginny Newell ’78 Arts Fund, which allows students to take summer internships outside the scope of North Carolina or their hometowns. She loves connecting with each new recipient and supporting them beyond the boundaries of their internship or grant.

“Being in the fourth quarter of life, I'm finding great pleasure being in a position to help people in the first quarter,” she said. “I love to see where they go.”

Arts grant recipient Julia Conley ’23 spent the summer of 2022 interning with Davidson alum and art consultant Alex Stoller ’09 in New York City. The experience allowed her to connect with a broader network of artists while immersed in the New York art scene.

“I am in awe of Ginny's courage in forging her own path and her generosity in wanting to support others in finding theirs,” she said. “By the end of our time together, I felt that I could take on the world.”

Most recently, Autumn Lee ’26 was selected as the inaugural recipient of the Virginia E. Newell ’78 Scholarship, established in support of The Davidson Trust for exceptional students who have demonstrated a passion for art history and/or the visual arts. The two have since bonded over their mutual love of art and science.

“This scholarship has made me feel more comfortable with my passion for art and the idea of pursuing it as a career,” Lee said. “Ginny has been a wonderful source of support in more ways than she knows.”

Since conservation skills require constant upkeep, Newell plans to stop working “cold turkey” once she retires. While she thinks she could be a good one-on-one resource for students interested in art or conservation, she’s mostly excited to relax and spread new roots in the Davidson community.

“My plan is to not have any plans,” she said. “I want to wake up, have a coffee and read a book out on my porch. Please stop by for a visit; the door is open."