Reaching Byzantium: The English Department Remembers Colleague Tony Abbott

January 8, 2021

- Author

- Davidson Journal

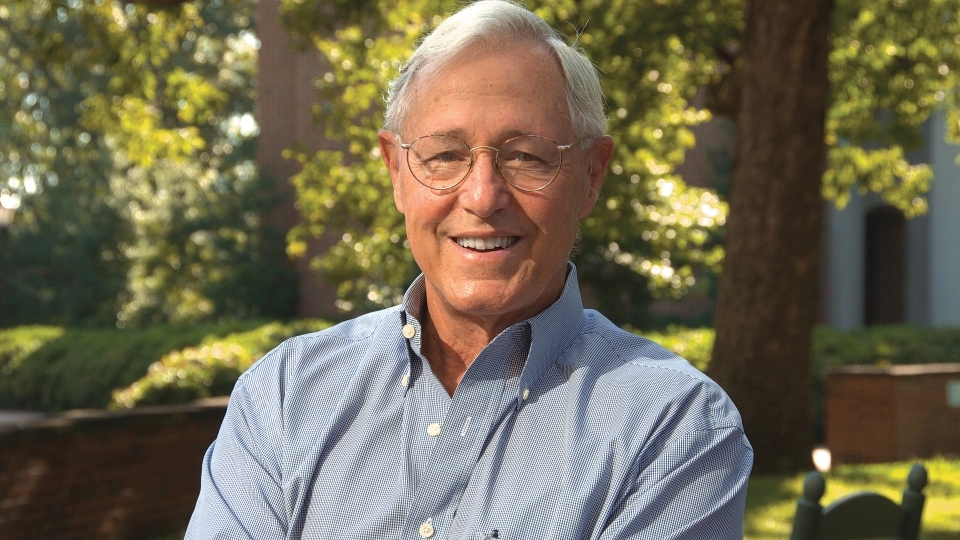

Charles A. Dana Professor of English Emeritus Anthony S. Abbott passed away Oct.3, 2020. Here, colleagues remember the light he brought into their lives as a scholar, teacher, mentor and friend.

The great teachers in our lives win us to their cause, for the most part, one day at a time. Yes, they all have a certain genius about them; but I’ve come to believe that their real talent is consistency, leading us toward our own discoveries and our own potential with grace and patience. Such an effort takes time; and, I am convinced, it was Tony’s defining trait as a teacher—the ability to engage his students in terms of seasons, decades, lifetimes.

He taught in dozens, maybe hundreds, of classrooms and venues, all of them immaterial to him. It was the students he focused on, teaching not through lecture so much as through a kind of gentle conversation and inquiry that put text and context into moments that people recognized with both mind and spirit. Tony searched out and exampled the overlooked miracles in our lives. Expressed them beautifully in his writing. A girl in a yellow raincoat. A man who believed in angels. Finding the miraculous within the ordinary, that was his grand and lasting subject matter.

But what I remember most about him was the magic. Give him a good book, shove him into a classroom, then stand back and watch. He absolutely exemplified the old Japanese proverb: Better than a thousand days of diligent study is one day with a great teacher.

—Randy Nelson, Professor Emeritus

In 1988, before the most recent Chambers renovation, my office was next to the room in which Tony taught the always maximally enrolled Modern Drama class. The room had a small 10-inch worn out riser running the length of the blackboard and more than its share of laughter and applause but was otherwise an ordinary classroom. But one day, as I was rounding the corner on the way to my office, there was a thud and a scream in the room, followed by the tell-tale scraping/screeching of desks being moved rapidly, and the shuffle of many feet. Then two people ran out of the room yelling seemingly at each other and at no one in particular: “Call 911! Call 911! Dr. Abbott has just had a heart attack!“

In those pre-cell phone days, there were phones on each floor of Chambers, but my office was closer. So I offered the use of my office phone for the purpose and rushed to unlock my office door, but before the students could put the phone to good use, Tony appeared in the door frame, smiled an apologetic yet gleeful smile and said that he was fine. He offered no other explanation. Later I would learn that falling off the podium while clutching at his chest was just Tony’s way of memorably making the point about the connection between breaking the fourth wall and Brecht’s use of that technique for alienation effect (Verfremdungseffekt), a theatrical step designed to disrupt and prevent the audience from identifying with, or unthinkingly taking for granted the action on the stage. I was to be an earwitness for five more of Tony’s Brechtian heart attacks. The first of those five resulted in a serious bruise but was still followed by four more because for Tony teaching was always a special calling. Some part of Tony seems to have been set apart for dynamic devotion to the needs of others. I am certain that those who witnessed Tony’s Verfremdungseffekt never forgot the lessons that went with it.

—Zoran Kuzmanovich, Professor

“He was a man take him for all in all”: The Tony I knew was a complex person. Yes, he was a great teacher who adapted his style, scholarship, and subject matter over the many years of his career. But I also remember coming into his office early in my career with the English Department and seeing a big bottle of Maalox on his windowsill. I wondered about that, so I asked. “Stress,” he said, pointing to his abdomen. Tony excelled in the classroom, but he also worked and worried in the process. There were so many other dynamic professors in the department with whom he was competing. We may say he was a “natural” and teaching was his passion, but I think he found the work demanding, physically as well as intellectually.

Despite his success with his scholarly publications, Tony sought other, more personal ways to share himself. He knew he could teach the work of others and organize his colleagues to spread that word, but later he found a new freedom in expressing his own inner life through both fiction and poetry. He brought the same discipline he had in other areas into these self-expressive creations, working and worrying. Yet, when he read one of his poems to a group, he did not read but recited, pacing around, waving his hand up and down to emphasize the rhythmic sounds. It was as if he were releasing the words from his gut. Surely a better cure than Maalox!

“I shall not look upon his like again”!

—Elizabeth Mills, Professor Emerita

Tony believed in people, in our capacity to learn. My only attempt at water skiing happened at the Abbott lake house, and though a rapid thunderstorm blew up before I could get up on the skis, only Tony could have convinced me to try and made me believe I could succeed. In this October of illness, fear, and division, we pause to celebrate Tony—his creativity, his compassion, his joy in community. He will live on for me in poetry readings that make me cry and lake sunsets so beautiful they exceed language. I may never get up on water skis, but thanks to Tony, I’ll keep trying.

—Shireen Campbell, Professor

Like W. B. Yeats, one of the many poets he taught and admired, Tony’s writing drive never waned, but seemed only to strengthen in intensity over the years. In “Sailing to Byzantium” (a poem written in his seventh decade), Yeats writes of the creative powers that keep an “aged man” from becoming a “paltry thing”:

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence.

Truly, Tony clapped his hands and sang, and louder sang—right up until his last days on earth before he sailed to some holier city. He lives on in the poems he left behind (“monuments of…magnificence”) and in our hearts, as kind and gentle teacher and leader.

—Suzanne Churchill, Professor

I first met Tony Abbott in August of 1983, during orientation for new students. I was the first in my family to attend college, and although I grew up in North Carolina, Davidson seemed to my parents and me a different planet. Our old Datsun hatchback felt like the rustiest car in satellite parking; even the clothing of Davidsonians seemed alien (alligators, polo players, names of outdoor supply stores and private schools). The three of us were quietly anxious all weekend, until the time came for my parents to meet my pre-major adviser, Tony Abbott. When they returned from that meeting, my parents were visibly more relaxed, their shoulders looser and their faces smiling softly. My father said, “You’re going to be okay here.”

—Randy Ingram, Professor

In late July, 1983, the week I moved to Davidson, Tony showed up at my front door. It was a stifling, hot day and there were still piles of unpacked boxes in my living room, but Tony had come right over as soon as he heard I was in town. He wanted to give me a fall semester Humanities syllabus and he wanted to talk to me about the Humanities program, its devoted staff and wonderful students. It was a long and engaging conversation, this first conversation in Davidson, and I remember almost everything about it. But what sticks out in my memory clearest about that afternoon is when Tony paused to pick up a framed photograph of my then-two-year-old daughter from a table, looked at it a long time, and then said to me that she reminded him so much of his own daughter. “Oh,” I said. “What is your daughter doing now?” “She’s an angel now,” he said. “She’s my muse. She’s my best self. She’s never left my heart.”

One of the last times I saw Tony Abbott, shortly before I retired and moved away from Davidson, he was reading from his Angel Dialogues poems at The Carolina Inn. Throughout the reading, I was remembering that first earnest meeting with him in my new Davidson living room and thinking about how he had been for so long a teacher and a poet touched by an angel. And here’s the truth: Anyone who has known a friend and a teacher and a poet touched by an angel knows that luminous person will never leave her heart.

—Gail Gibson, Professor Emerita

This article was originally published in the Fall/Winter 2020 print issue of the Davidson Journal Magazine; for more, please see the Davidson Journal section of our website.