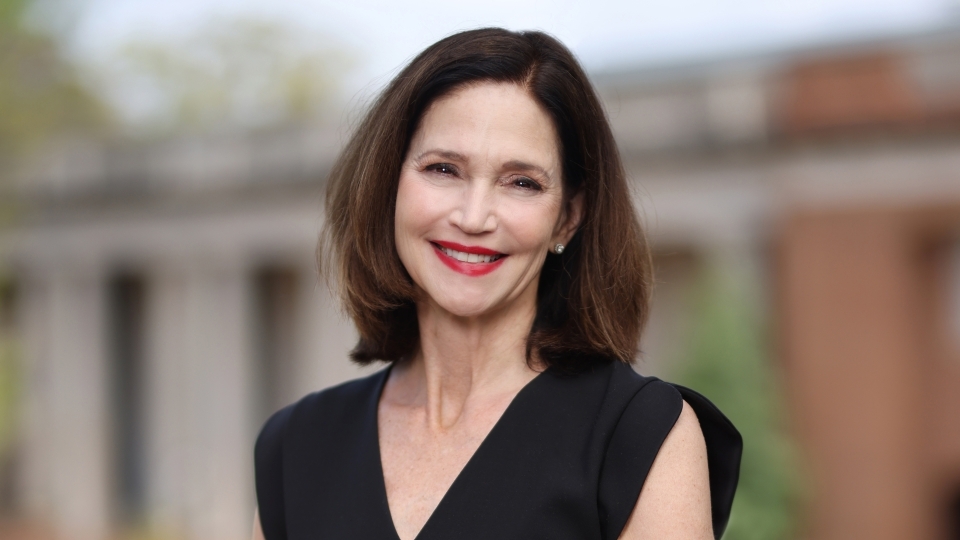

Risk and Reward: President Carol Quillen’s 11 Years of Bold Achievement

June 14, 2022

- Author

- Mark Washburn

Mackey McDonald’s speech was scripted like a thriller.

On May 26, 2011, he opened by thanking the presidential search committee for its diligence, noting they’d landed a candidate who would protect Davidson’s values and traditions, but one who had a vision to prepare students for a rapidly changing world.

Halfway through, after an inventory of credentials, he let it slip that the candidate was a “she.” There, Mackey ’68 took a dramatic pause, letting the reaction rise. Davidson, it was evident, had reached yet another milestone moment.

Then, finally, the big reveal. “Let me introduce her: Davidson’s 18th president, Carol Quillen.”

Ask McDonald 11 years later how the vote that morning by the Board of Trustees he had chaired worked out and he is unequivocal, no delayed reveal.

“Carol continued to provide unmatched leadership and wisdom throughout her time,” he says. “Davidson is a much better school because of her time in office.”

Risk didn’t seem to be a factor in Quillen’s appointment. Though she’d never been a college president, she’d risen through academic ranks throughout her career with deep administrative experience at Rice University in Houston, where she’d been recently named vice president for international and interdisciplinary initiatives.

Yet, no question, she was an unconventional choice. Until 1972, when trustees voted to admit women, Davidson had graduated only men for its first 136 years. And she lacked a Davidson diploma.

She acknowledged as much in her remarks that day, striking a confident yet humble tone.

“I come to you, I know, from outside the Davidson family. I have much to learn, and it would be beyond presumptuous—as well as unwise—for me,” she said, “to talk too long, when what I most want and need to do is listen.”

Two takeaways: She listens. She’s humble.

Actually, three takeaways, though no one suspected it at the time.

Hold on to that word “risk.”

Recognizing Her Roots

Quillen says she wasn’t deeply familiar with this small, Southern college of about 1,900 when she was first contacted by an executive search firm, but recognizes now the opportunity came at a perfect time.

Her husband, Ken Kennedy, who taught computer science at Rice and was considered a pioneer in the field, had died of pancreatic cancer in 2007, and her daughter, Caitlin, was about to enroll at UNC Chapel Hill.

When she met the search committee, she was impressed. “It was composed of people all dedicated to leaving the world better than they found it,” she says.

After 21 years in big-city Houston, she was ready for a walk-to-work job in a small town a bit like her hometown.

In Delaware, New Castle is a know-every-neighbor community of about 5,000 just south of Wilmington. It still wears its colonial vestments. Founded in 1651 by Peter Stuyvesant, some of the town’s buildings are ancient by American standards. Among them is the original 1732 courthouse where Delaware’s license-plate slogan “The First State” was earned in 1776, when its state assembly was the nation’s first to declare independence from Great Britain. Harriet Tubman came later with the Underground Railroad.

Quillen grew up on a street fronting the Delaware River. She could walk to the penny candy store downtown. It was the kind of place, she says, where people looked after one another and cared about the community.

There, the Quillens attended New Castle Presbyterian Church, whose Meeting House dates to 1707. Her family has an American Dream storyline. Her grandfather, a car dealer, never attended college. Her father went on to be a Harvard-educated attorney, later a judge and then Delaware secretary of state. He ran unsuccessfully for governor once. Today, her sister, Tracey Quillen Carney, is Delaware’s first lady, wife of second-term Democrat John Carney.

Both sisters attended Wilmington Friends School, founded 1748, from kindergarten through high school. Its Quaker values hold that everyone has a unique and immeasurable dignity commanding respect of all, and that learning is a never-ending process of exploration and discovery.

Tracey, one year younger, and Carol both excelled on the field and in the classroom.

“I liked books more than people,” Carol says, though she played field hockey and basketball.

Tracey, whom Carol says was the far better athlete, says her sister couldn’t match her own “killer instinct” in sports. Even from childhood, Carol was more of a, well, team player, striving for collaboration.

“I am an introvert,” Quillen admits. “I feel like I live in my head a lot. Engaging with others sometimes takes energy.”

She’s not into chit-chat, perhaps a professional disability, and is more drawn to substantive conversations. Staff at Davidson quickly adjusted to the realization that, when they met with her, she would have an abundance of tough questions about whatever they were proposing. They knew they had to do their homework and defend their ideas.

Era of Risks of Reckoning

Ask people about Quillen’s style and many of the same observations keep popping up.

Good listener. Bold vision. Empathetic. Warm. Collaborative. Thinks big thoughts. Introverted, but fearless on stage. Always pushing for excellence. Always asking, how can we get better?

And a common refrain: She took big risks.

Big risks, as in reimagining the campus science center as a crossroads of disciplines. As in launching a fund-raising campaign that would exceed ambitious goals and come in at a half-billion dollars. As in shelving idiosyncratic Davidson institutions like laundering students’ clothes. As in leaving the decades-long comfort of the Southern Conference for a far more intimidating athletic stage.

And, as in inviting a deep and disquieting inquiry into the college’s racial history, antebellum and beyond.

In 2017, in the wake of the Charlottesville violence and the growing national reckoning over race, Anthony Foxx ’93 took a call from Quillen. She had a big–and bold–ask: It’s time to explore the college’s historical roots and relationship to slavery and racial injustice. Would you chair the initiative?

“My knees were shaking a little bit more than hers were,” says Foxx. “But that shows you who was the more courageous one.”

Foxx—former Charlotte mayor, transportation secretary in the Obama administration and Davidson trustee—said “yes.”

Foxx didn’t expect the Commission on Race and Slavery to be universally praised. And there was blowback to the announcement from some who questioned the motives of administrators and the direction of the college.

But Foxx says he understood that while some might feel threatened, some might just want to forget, and others might just think it was time to move on, it was critical to the college’s mission to confront its past to ensure better times to come.

“I knew our institution needed to evolve to be relevant in the present and the future,” Foxx says. “It served no one not to have a holistic understanding of our past.”

Quillen, ever the historian, warns if you leave it buried, the past eventually emerges, unbidden and violent, into the present.

“A lot of people think if you ignore the past, it goes away,” she says. “But the past is always here, and a past unexplored is dangerous.”

What emerged in August 2020 was a blunt chronicle of Davidson’s fraught racial history dating to the founding in 1837.

Many founders—names like Davidson, Morrison, Chambers—were enslavers. So were early faculty members.

Enslaved persons cast bricks for original buildings. Mock lynchings were performed on campus as late as the 1920s. Trustees in 1961 decided to admit Black men only if they were international students. Black Americans were finally admitted in 1964. Deep into the 1960s, “Dixie” was played at football games. Charles Dockery, French professor and the first Black faculty member, wasn’t hired until 1974. It would take until 1992 for the first Black student body president to be elected: A history major from Charlotte named Anthony Foxx.

Quillen issued an apology on behalf of the college and the Board of Trustees.

“As an institution with moral responsibility,” she said, “Davidson College affirms our commitment to acknowledge fully wrongs of the past, and to act now and in the future for a just and humane campus and world.”

Immediately, Davidson pledged to hire four tenure-track professors partly or entirely in Africana Studies, including a public historian. Student research projects were based on the committee’s study. A committee was born to address research inquiries, requests and collaborations with community groups. Hilary Green, a scholar of Civil War and Reconstruction at the University of Alabama, joined Davidson as a Vann Professor of Ethics in Society. Ad hoc committees were set up to examine commemoration and naming of facilities.

Quillen championed the concept of “campus as gallery,” integrating art into daily life on campus, through sculpture, student exhibitions and displays from the college’s extensive permanent collection. The college added its fifth outdoor sculpture in 2013 (pictured here), “Waves III” by Spanish artist Jaumé Plensa.

Diversity Always at the Fore

Already, Davidson had made strides in broadening its diversity. It had revised hiring and recruiting practices to look in new sectors. Human Resources and the faculty created search processes that identified talent that Davidson might have missed before. Even the Board of Trustees joined in, identifying younger graduates who were remarkable candidates for board seats.

Quillen oversaw the broadening of minority talent in the executive ranks with the hiring of Chris Clunie ’06, the first Black athletic director; Byron McCrae, first Black vice president for student life and dean of students; Ann McCorvey, first Black vice president for business and finance and chief financial officer; and Philip Jefferson, first Black vice president for academic affairs and dean of faculty, recently sworn in to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

During Quillen’s tenure, the student body also grew more diverse, racially and socio-economically. In 2010, there were 96 domestic students of color in the incoming class. Last year there were 143.

“If your applicant pool is diverse, you’re going to build a diverse community ,” Quillen says. “As we focused on equitable search processes, diversity happened.”

Melting Boundaries Through Architecture

Early in her term, the time came to renovate the Martin Science (chemistry) Building, built in 1941. Erland Stevens, who started teaching chemistry at Davidson in 1998, gave Quillen a tour.

“He told me that the periodic table of elements had changed more since the building had been built than the building had,” she recalls.

So the question became, what should replace it? Simple, many reasoned. You take a Bunsen burner and build a chemistry building around it.

“She was, like, ‘Why just revamp it?,’” says Julio Ramirez, R. Stuart Dickson Professor of Psychology, whose nationally-recognized research focuses on recovery of function after central nervous system injury and has profound implications for future treatment of Alzheimer’s and similar disorders.

“One of her favorite phrases is ‘reimagining the liberal arts,’” he says. “She pushed us to think about what could happen at the interface of science and arts and humanities.”

It was a $74 million reimagining. The gutted Martin Building retained its historic facade. Added to it was the E. Craig Wall Jr. Academic Center, designed to promote joint study and research in chemistry, biology, psychology, neuroscience and environmental science.

The building functions as a vibrant center for the arts, lectures and other gatherings. It also beckons thoughtful exploration beyond the ramparts of a single discipline, creating a space where various specialties intertwine in eddies and whirlpools of discovery, a misty membrane where interesting stuff happens.

One of her favorite phrases is ‘reimagining the liberal arts.’ She pushed us to think about what could happen at the interface of science and arts and humanities.

“Unintended collisions” is what Quillen calls them.

“You never know what kind of ideas are going to pop up when you bump into colleagues,” Ramirez says. “What has taken root is precisely what she wanted.”

Perhaps an unintended nod to its chemistry origins, Quillen insisted the building honor the fusion of silicon dioxide, calcium carbonate and sodium carbonate. Non-chemists call that glass, and it is everywhere.

Professors’ offices have glass doors, glass walls. Same with classrooms. Light pours in through each exposure. Random comfy nooks invite students to plop down and study. Whiteboards are everywhere, mostly ablaze with student scribblings—a complex molecule diagrammed here, a lab rat depicted there. Tables and chairs are all on rollers. Any room can reconfigure in seconds.

Ramirez points with pride to a physical manifestation of what occurs at the intersection of science and art. One of his students, Adrienne Lee ’21, grew conversant in both. She crafted a plasma-cut steel sculpture, a skull-shaped dome, that describes the neural connections of the brain. “Tell Me Where Is Fancy Bred, Or in the Heart or In the Head,” she titled it. That’s discipline No. 3: English lit, a line from Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice.”

Another specimen: The four-story atrium—where a grandstand-style arena faces a huge screen where lectures, student art and other ephemera flicker on command—includes Ten Days, a collaborative project between painter Herb Jackson ’67, Douglas C. Houchens Professor of Fine Arts Emeritus, and poet Alan Michael Parker, current Douglas C. Houchens Professor of English. Jackson, who arguably elevated Davidson’s art department to the national stage before retiring in 2011, produced 10 drawings, and Parker wrote 10 poems, which were paired in this lyrical installation.

They each did their part independently over 10 days, then revealed to the other what they had created. To their astonishment, they found that pieces were connected in almost mysterious ways. Afterward, they wed the components thematically.

Just nine paces away, visible behind a wall of silicon dioxide and its nimble partners, squats a nuclear magnetic resonance device for chemistry experiments.

Challenging Idiosyncrasies

Quillen found a Davidson steeped in tradition, with some unusual quirks. Since 1925, for example, the college had washed students’ clothes. A shocker, she says. “It was a, ‘Wait. What?’ moment.”

She had done her own laundry while collecting history degrees at the University of Chicago and at Princeton. It seemed to her that the resources could be better used elsewhere. In 2015, Davidson announced it would end the perk.

“To me, it wasn’t fitting with the place we were trying to become,” she says.

Change can startle. Larry Dagenhart, the 1953 class valedictorian and a proud alum, bemoaned the move at the time, telling the Charlotte Observer: “We gave up vespers, we gave up chapel, we went coed, we even gave up the marching band, but dad-gum-it, we can't give up the laundry. What is this world coming to?”

It came to this: Now the old laundry is the Lula Bell Houston Resource Center, where students can go for food, interview clothes and text books.

After the din subsided, Quillen learned the decision was not only broadly supported, but it also revealed another Davidson distinction: openness to change.

“It helped me understand that my instincts weren’t wrong,” she says. “Davidson is a place where people are more willing to make changes than other places in academia. It is a scrappy place.”

Changing Conferences

Carol Quillen the introvert doesn’t attend basketball games. Carol Quillen the hooting, jumping, arms- windmilling-while-calling-traveling on opponents shows up. She pops from seat to seat.

“I get nervous,” she says. “It’s funny. I want us to play well. Pacing helps me be less obnoxious as a fan.”

Chris Clunie ’06, former Davidson basketball player and now athletic director, says Quillen is, in all sports, the Wildcats’ No. 1 fan.

“I’ve told her now that she doesn’t have to be a prim college president,” he says. “You can let loose and tell the ref what you really think.”

Quillen says she didn’t come to Davidson to become the sports president, but the college’s athletic program took its biggest, boldest leap two years into her term.

Behind the scenes, the athletic department was agitating to compete on a bigger stage, test itself in more demanding arenas.

So in 2013, Davidson announced it would be leaving the Southern Conference, its home since 1936 and where it was a perennial No. 1 in basketball, to join the larger and more competitive Atlantic 10.

Davidson became the smallest college in the A10. Its Big Three members—George Mason University, University of Massachusetts and Virginia Commonwealth University—have enrollments above 30,000 and vastly more scholarships to distribute.

Media predictions for men’s basketball rolled in: “Dead last” and “0–18.” Coach Bob McKillop joked he would call former Wildcat standout and NBA star Stephen Curry to see if he could use his final year of eligibility.

Costs would soar. Rather than riding a bus to regional rivals, athletes would have to fly. Davidson would have to pay a $600,000 exit fee to the Southern Conference and an expensive entry fee into the A10.

But there were attractions. Exposure would soar, too. It would bring the Wildcats to big media markets in the Northeast and Midwest, where it could connect with more alumni. Costs would be offset by bigger revenues from TV contracts with the A10. ESPN, CBS Sports and NBC Sports would televise men's basketball nationally.

“I think it’s been one of the greatest decisions the college ever made,” says McKillop.

Alumni got behind the move and helped bankroll the athletic budget. Recruiting grew more robust. Quillen was in absolute lockstep with the athletic department, McKillop says, in making the jump.

As for the dire media predictions?

In their first year in the A10, the Wildcats finished 14-4 in basketball to win the A10 regular season championship. Sports Illustrated admitted the team had “outpaced the expectations of even the most wide-eyed dreamer.”

And on it rolls. This season, Davidson was No. 1 in A10 basketball with a 15–3 conference record and a bid to the NCAA playoffs. And those Big Three schools? Davidson beat them all, at least once. And, in case you don’t follow the sport, Davidson beat the University of Alabama as well, 79–78, in Birmingham.

The Wildcats watch scoreboard highlights after defeating the Rhode Island Rams in the championship game of the Atlantic 10 basketball tournament at Capital One Arena, in Washington, D.C., on March 11, 2018. Davidson jumped from the Southern Conference to the more competitive A10 under Quillen’s leadership.

Clunie says the success of Davidson athletics is all the more remarkable when considering its size, one of the smallest Division I colleges in the nation.

“It’s hard to be a Division I scholar-athlete,” Clunie says. “It’s even harder to be a scholar-athlete at Davidson.”

There are no special residence halls for athletes, no separate cafeterias. Scholar-athletes are expected to complete their studies like everyone else, without special tutoring.

Most of Davidson's peer colleges—small, private, academically ambitious liberal arts institutions—compete in Division III. It’s rigorous and demanding for those who play Division I.

“Athletes are still 100% athlete and 100% student 100% of the time, despite greater demands,” Davidson soccer star Andrew Kenneson ’16 wrote in The Davidsonian in 2016, describing the pressure his senior year. “Even after a move to a bigger conference, Davidson treats its athletes like regular students.”

Clunie, a Terry Scholar, basketball player, and Watson Fellow as a student, says he was drawn to return to Davidson in part because of Quillen’s philosophy on how athletics is vital to a student’s education.

“Carol’s the best person I’ve ever worked for. … She sees the educational value of athletics—resilience, teamwork, stress under pressure, critical thinking,” he says. “Athletics enhances that educational mission. It’s not the four years when we’re here that you have to think about; it’s the 40 years when we’re gone.”

Quillen says 99% of scholar-athletes won’t go on to professional sports, but embraces the role it plays in Davidson’s holistic education.

“We play sports because sports are part of the educational experience,” she says. “My beef with intercollegiate sports is that some lose sight of the educational value and focus completely on the competitive aspect. Students are here to be educated. We’re not a minor sports league. No school should be.”

Celebrating President Quillen's 11 Years of Leadership

Paying the Bills

Money is the lifeblood of every college. Fundraising is a critical role for any leader.

In 2012, The Duke Endowment made a gift of $45 million. In 2013, Davidson announced a plan to spend $120 million in capital improvement projects over the next decade to re-engineer the campus with an eye to more integration among academic departments, with a new science center high on the list.

In 2014, Davidson announced a stunning goal: $425 million, the largest drive in the college’s 177-year history, to bolster its scholarship fund and pay for expansion. That campaign raised more than half a billion dollars; another demonstration of support from an alumni body that consistently places near the top of alumni giving participation nationwide. Davidson’s endowment mushroomed past $1 billion.

Compliment Quillen on how the Davidson Trust prospered during her time and she humbly defers to a predecessor, Bobby Vagt ’69, who launched the initiative in 2007. Davidson became the first liberal arts college to offer need-blind admissions through the Davidson Trust, meeting 100% of demonstrated need without packaged loans, thus broadening its reach to students of lower income families.

During her term, Quillen emphasized scholarship fund-raising, bringing in more than $285 million. Quillen and her husband, George McLendon, pledged $1 million themselves in 2017.

Other Landmarks Emerge

Like most colleges or universities, Davidson’s faculty of 200 has twice as many opinions. But when a space dedicated to innovation and entrepreneurship was proposed, it is fair to say the faculty was baffled.

Quillen wanted to take an industrial space in the old Davidson Cotton Mill, circa 1920, across Main Street from the college and launch in 2018 what would become known as the Jay Hurt Hub for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, a 23,000-square-foot facility for teaching, research and office space for businesses. Critics pointed out that it was an unusual, if not revolutionary, facility for a liberal arts college.

Such facilities are typically found at big research universities that create biotech or engineering advances. Davidson doesn’t have a medical school, an engineering school or a center developing technology to monetize. But it took off from the start.

Now, it is a high-tech, rough-hewn, 23,000-square-foot dynamo where campus brainpower and local minds gather to create. Student companies have sprouted there and established firms come seeking talent. As a center of innovation, it appears to be growing organically, Quillen says. “It evolves. I don’t know what it will become.”

Quillen is known for her broad concern for the role of a liberal arts college in the 21st century and how to stay relevant against competitors like online educators. She often talks about how the liberal arts cultivate the deep human skills that employers seek, such as finding connections between disparate problems or communicating across a diverse group. And she adds that, what they also need, are the more technical skills that prep them for day one.

Preparing students for lives of leadership and service should include launching them into meaningful careers; she wanted to ensure Davidson gave graduates the direction they needed to succeed.

For that, Quillen poured resources and energy into the Betty and B. Frank Matthews II ’49 Center for Career Development. There, students are coached, from freshman year onward, on how to channel their academic knowledge into internships, fellowships, graduate degrees and jobs. Under the direction of Executive Director Jamie Stamey, the center connects students with opportunities and employers from around the world and follows up after graduation to measure how students fare.

Dealing with the Unexpected

Leadership is defined by dealing with challenges. It’s easy to lead in good times and flush with money. COVID-19 was about as far from a good time as one could get.

Quillen kept the ship of Davidson steered toward a clear destination: Fulfilling its mission within the context of the circumstances around it.

Uncertainty mounted. Phases rolled through. Case numbers spiked and fell. Staff and faculty created ways to connect without increasing risks, from Zoom open mic night to outdoor faculty office hours. The staff forged new techniques for serving meals safely.

Quillen showed up everywhere. She answered questions from anxious faculty and students in town hall meetings, and convened and led a team that coordinated the college’s response—everything from making Davidson “test-optional” for prospective students to equipping the classrooms with the technology to go all virtual to creating expert-informed safety practices and policies.

When the dining hall fell short of staff, Quillen and other staff signed up for shifts, pulled on aprons and plastic gloves and started serving the chow line.

She marshaled the resources to make it all happen and worked alongside the people behind the scenes who were doing new and different work every day. And she cheered them on.

“I want to thank you for your empathy and courage,” Quillen said in a 2020 address to the campus. “Students, faculty, staff all have pushed past the sadness and anxiousness. You’ve poured yourselves into upending, then reconfiguring, how you do everything.

“You have bridged enormous distances to help others, to sustain and strengthen the incomparable sense of community we all cherish so much at Davidson.”

Change is born of a challenge. It also can invite it. Upending traditions and normalcy churns conflict.

“Leadership, to me,” Quillen says, “is in part helping people overcome their fear of loss so that they can reach high and imagine what might be possible.”

Even with its high standards and motivated principles, running a college like Davidson can be mentally wearying. So many quarters—students, educators, staff and alumni—demand and deserve attention. Conflict is inevitable.

McKillop, who coached basketball under four college presidents at Davidson, likens it to being president of a country.

“I learned a lot from her in terms of vulnerability,” he says. “She leads an incredibly diverse constituency. We’re dealing in a different culture than what Davidson was in the 1960s, 70s, 80s.”

It is challenging.

“I have seen the pain she’s experienced, the heartache she’s had in order to unite this distinctive but wide range of people Davidson has,” McKillop says. “She taught me how to weather those critics who are out there.”

“From my perspective, all the risks she took paid off,” says Ramirez, the neuroscientist. “It’s a good lesson for our students.”

Ask Quillen how she thinks she’s going to be remembered in, say, 100 years, and she dismisses the question. No one should care, she says. It’s a group project. It’s about being part of the community’s trajectory, exemplified by the presidency of Sam Spencer, when Davidson's doors opened to women. It’s about helping this special place recognize and seek to fulfill the promise of its founding.

Admiration From Afar

From the outside, advances at Davidson during Quillen’s administration have drawn attention.

“Carol Quillen established herself as an important and compelling voice in American higher education,” says Christopher Eisgruber, president of Princeton University, where Quillen earned her doctoral degree.

“She has led national efforts to get more low-income and first-generation students to and through college. She has spoken powerfully about humanistic education and its relationship to the ethics of citizenship,” Eisgruber says. “She is a force for good, ever faithful to the values of learning, and both respected and liked by her counterparts throughout the country.”

Her impact is well recognized, as well, by the Board of Trustees.

“From the start, Carol had extraordinary vision,” says Alison Hall Mauzé ’84, board chair. “Reimagining liberal arts was something she talked about early on. She was always looking for ways to bring people together.”

Development of the Hurt Hub, Mauzé says, allows Davidson students to find new pathways for their talents. Emphasis on career development pushed forward the college’s mission, too.

She credits Quillen with taking a courageous stand by supporting Davidson’s own statement to support academic freedom on behalf of the faculty, drawing attention nationally.

In her 11 years, Quillen has markedly strengthened every corner of the college—finances, academics, athletics, diversity, Mauzé says. She has set Davidson on a firm and prosperous platform ensuring future success. She has left it better than she found it.

“I think she has extraordinary courage, one who empowers and supports her team,” says Mauzé. “She’s a pioneer, thoughtful, kind and the most humble leader I’ve ever worked for.”

Mauzé says Quillen left her successor with “very big high-heels to fill.”

Additional Coverage

Hurt Hub Gift Inspired by Family, Liberal Arts and President Quillen

Quillen Joins Princeton Board of Trustees

Gifts Honor President Quillen’s Transformative Leadership

$10M Commitment Names Fieldhouse, Honors President Quillen’s Leadership

This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2022 print issue of the Davidson Journal Magazine; for more, please see the Davidson Journal section of our website.