Alum Leads Navy Battle With Pipettes and Vials

November 11, 2020

- Author

- Mark Johnson

During their time in Ghana, Andrew Letizia ’99 and Jenny Nolan Letizia ’99 hosted Davidson Ghana program. They’re pictured wearing outfits Jenny custom-designed.

A doctor who ensures that U.S. F-18 fighter pilots based in Japan are flight ready doesn’t appear as the most likely candidate to have studied Greek and Latin, Homer and Cicero.

Nor does a researcher sequencing genes to fight viruses in West Africa, or an infectious disease expert studying COVID-19 among Marine recruits on Parris Island.

U.S. Navy Commander Andrew Letizia, with a classics degree from Davidson College, is all three.

The minister’s son from Long Island counted himself among the half of Belk Hall freshmen that did NOT want to go to medical school. Yet he ended up a doctor at the front of both the pandemic and national security.

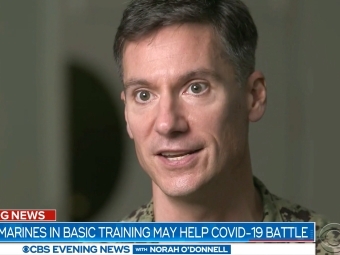

U.S. Navy Commander Andrew Letizia ’99 is interviewed for a CBS News piece on a cutting-edge study he led to understand how young people’s bodies react to the novel coronavirus.

Letizia, class of 1999, knew he wanted to explore art, architecture, engineering and English—most of the campus map. He snared roles in three theater productions and developed an itch for travel. His Dean William Holt Terry scholarship enabled him to study abroad so much that the program’s namesake asked: “Why don’t you like Davidson?”

Between sophomore and junior year, Letizia applied and geared up for a summer archaeology trip to Cyprus but didn’t make the cut. He scrambled and put together a trip to work at a tuberculosis clinic in Bangladesh run by an alum. After that, he hopped a train and bus—a boat, too, he thinks—to Calcutta and spent a week volunteering at Mother Teresa’s home for the dying.

Along the way, he found the nexus of his mashup of interests.

“Where it all comes together for me is in infectious disease,” Letizia said, “not just on those afflicted—on the economics, the utilization of scarce resources, ethics, history—history was written with the morbidity and mortality of infectious diseases…I got to understand where my talents could best serve. I got to understand aspects of clinical care and what we’re starting to call global health.”

His new medical school trajectory brought the military onto his radar because of both the scholarship and the natural fit for someone focused on infectious disease.

“We have young, healthy people all over the world exposed to all sorts of disease risk,” Letizia said from his current headquarters at the Naval Medical Research Center, in Maryland, where he is deputy director of infectious disease research and head of the emerging infectious disease department. He leads 17 officers, 125 civilians and a $20 million budget.

After medical school at Mt. Sinai, in New York, his internships and residencies took him to the Naval hospital in San Diego and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, in Maryland. He earned a master’s degree in tropical medicine and advanced to roles of increasing responsibility, from a flight surgeon in Italy to supervising other doctors in Japan to officer-in-charge of the Navy’s medical research unit in Ghana.

Along the way, he and Jenny Nolan Letizia, an art history major and architectural designer from the same class at Davidson, got married and now have three children.

At Ghana, Letizia established the gene sequencing capability at the Navy’s unit, creating immeasurable capacity for diagnosing viruses and creating vaccines. The key was putting native Ghanaians in central roles, extending capabilities beyond the Navy itself.

“The more we can stand up independent sentinel sites around the world for these tropical diseases and emerging viruses, the better,” he said. The Letizias played host twice to Davidson’s Ghana program during their three years, and Jenny custom-designed red outfits with Davidson’s logo and outlines of Ghana.

Pandemic Response

The Naval Medical Research Center, Letizia’s next and current post, leads research on the effects of everything from SCUBA diving to flight to trauma to infectious disease—his wheelhouse. His team zeroes in on all manner of viral pathogens, and in January that meant the weird new disease emerging in China.

Letizia credits Davidson with not only offering the latitude to explore disciplines and geography, but helping cultivate the deep skills to forge into the unknown. And nothing was more mysterious and foreboding in January than the novel coronavirus.

“He throws himself wholly into anything he’s doing,” said Dirk French, professor emeritus of classics and Letizia’s adviser.

The Navy formed a crisis response team from various fields. How would they diagnose this new pathogen on a ship and prevent spread? (Try physical distancing on a submarine.) Members of the Naval Medical Research Center’s team deployed to the USS Theodore Roosevelt aircraft carrier during an outbreak in March that infected 1,200 sailors and killed one. Testing at this stage was complicated, cumbersome and slow.

As the pandemic spread, Letizia benefitted from the adaptive culture of Davidson combined with the military’s tendency to immerse personnel in multiple roles inside and outside their job description.

The Navy had a challenge. The Marines, which are a branch of the Navy (but don’t say that to them), do two things: win battles and ‘make’ more Marines. COVID 19 was spreading on the storied Marine training base at Parris Island, South Carolina, where new recruits train.

“The military is good at telling you what the goal is and equips us with the resources we need,” Letizia said. “You’re able to slow things down and deal with the bite-sized bits you can control to ultimately accomplish the mission.”

His team needed to look at the cells in the immune system that teach memory and how they communicate with each other, how they create antibodies. To do that, they needed to ask Marine recruits to volunteer for a study, after receiving a brief on the project and signing an informed consent form. The study included drawing blood, extracting the special immune cells, freezing them to -80°C and getting them to a lab. The team included 19- and 20-year-old Navy corpsmen with little or no lab experience.

“There’s an emphasis at Davidson that you have to be humble and rely on your team,” Letizia said. “This was very sophisticated testing, and we were able to teach these corpsmen how to do this in a college auditorium and a hotel ballroom.”

The team faced a universal shortage of testing equipment, including a special broth for growing virus that normally comes in three-millimeter vials. They haggled and cajoled their way to 30 liters and, then, pipetted it into tiny vials.

Letizia and his team, working at and around Parris Island in early May, needed to figure out who was sick, symptoms or not, how many more people they would make sick and how quickly. They needed to better understand the immune process, which would help toward a vaccine and therapeutics. At that time, virtually every college and university had sent their students home.

“We were the only large cohort of young, healthy Americans from primarily the east coast,” he said.

Letizia lauded the recruits, already enduring a physically and mentally exhausting boot camp, who provided saliva, nasal swab and blood tests six times in eight weeks.

Letizia and colleagues published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine this week that outlines how easily COVID spread. One percent of the new recruits who arrived at Parris Island tested positive, despite quarantining at home and low risk factors. Of those who tested positive, 90 to 95 percent showed no symptoms. Recruits quarantined at a nearby college or a hotel for two weeks after arrival and, among those, 2 percent tested positive, despite the use of various public health mitigation strategies including using disinfecting wipes and other safety precautions.

The research led to an invaluable conclusion that infected young people with no symptoms spread it to others, and the vast majority will not realize they are infected.

The Naval research team, working closely with the Navy and Marine Corps’ public health departments, used the data to help the Marines establish protocols to mitigate spread of the disease. The resulting work even brought down cases of other upper respiratory infections, like the flu, as well as gastroenteritis, a virus in the intestines, and cellulitis, a skin infection.

“The result,” Letizia said, “was helping them figure out how to safely ‘make Marines’ in the middle of a pandemic.”