New Book on Cherokee Nation’s History Gets NEH Grant Support

March 3, 2023

- Author

- Lisa Patterson

Rose Stremlau, Associate Professor of History

Some records survived war, and the displacement and hardships faced by their authors. Those records are scattered, some labeled with euphemisms and filed haphazardly in boxes chaotically placed in government agencies.

Some records are lost to history—destroyed during the nation’s bloodiest conflict, carelessly tossed aside when homes were seized and their contents purged, or exposed to the elements as the inhabitants of those homes trudged the desolate path of forced relocation.

It's the job of the historian to surface the first-hand accounts and official records that remain and fill in the gaps left by those that no longer exist. With a $250,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Prof. Rose Stremlau hopes to do just that with a new, comprehensive history of the Cherokee Nation, one of the largest native nations in the United States. With colleague and co-author Julie Reed, of Penn State University, Stremlau is drafting an account of Cherokee history from pre-1600 to 2010. Stremlau says the book project, titled Sovereign Kin: A History of the Cherokee Nation, will be the first of its kind.

We spoke to her about the project.

What is the scope of the project, and what does it address that isn’t already available to scholars and the public?

For me, this project is more than 20 years in the making. I learned of the need for this book when I was a graduate student in the early 2000s and studying with a specialist in Cherokee history at UNC Chapel Hill. As I began reading the canon of Cherokee history, my advisor explained that there is no one book that gives a good, comprehensive overview because the book that was written for that purpose is dated—it was published in 1963. Frankly, it wasn't a good book in 1963. From that point on, her comment has echoed through so many conversations I've had, first as a graduate student and then as a scholar of the Native South.

I’m not unique in recognizing this need. My co-author, Julie Reed, also studied with the same advisor in graduate school, and she’s a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. She sees the demand for this resource for Cherokee leaders, tribal employees and educators, too. We share a commitment to ensuring that there is a current, accessible, and accurate source of information for students, policy makers, journalists, teachers, curators—folks who are interacting with Cherokee history and culture for all different kinds of reasons—and who don’t have time to do their own research or read multiple books.

Indian School, Cherokee, North Carolina. Copyright claimed by Herbert W. Pelton c1909. From the Library of Congress panoramic photographs collection.

Who is your intended audience?

We are writing for the folks mentioned above and for anyone who wants to pick up a good book on Native history at their local bookstore. We want this to be available in every museum gift shop in Cherokee lands from Oklahoma; through Tennessee, western North Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia; and at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. We want this book to be picked up everywhere from airport bookstores to college classrooms. We’d also like it to be used in teacher trainings in areas where Cherokee students are being taught.

We are writing for this broad readership because Cherokee history is very often the canary in the coal mine for Native issues. Most obviously, the Cherokee Nation is one of the largest Native nations in the United States. In addition, the footprint of Cherokee history is significant because much of federal Indian history runs through that Nation's history.

What most excites you about this project?

This is an amazing opportunity—it’s exciting to think about how widely read this book could be because both of us have spent much of our careers trying to engage broad audiences and doing public history work in Indigenous Studies. As we have conversations with journalists or work with folks who are doing history projects for the Nation, or who are working on teacher ed in Oklahoma, or working for their museum or cultural center, we recognize that they need this, that they've wanted something they can refer to and say, "Read this chapter." We know that this will make life easier for people doing the important work in their communities.

We also feel fortunate that we have the support of a half dozen readers, including the former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, a former Supreme Court Justice for the Cherokee Nation, and the director of the Trail of Tears Association, which is a large public history organization that works to mark the Trail sites, and to ensure that curriculum being taught about the Trail is accurate. We have the potential to create a model for how to do good, collaborative scholarship in ways that are supported by people in the community who have important perspectives and, in many cases, perspectives that differ from one another.

What are some of the misperceptions the book will address?

One that looms large in public perceptions of Native people in the South is this idea that Cherokees who acculturated, especially in the early 1800s before the Trail of Tears, meaning those who converted to Christianity, those who began to reorient themselves economically toward chattel slavery and plantations, were accepting the superiority of Anglo-American civilization. Cherokee history shows how Native responses to settler colonialism are both more complicated and interesting.

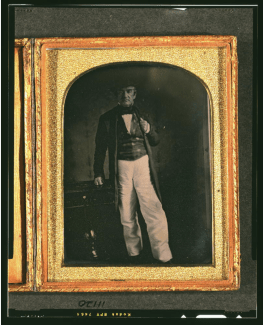

We begin each chapter with a vignette, and we're very intentionally picking people either who have not been covered by historians, or in some cases, providing new insights into people who have been written about extensively. For example, John Ross and Major Ridge are two men who get held up as examples of Cherokee assimilation in this period, and we complicate their stories. These very different men believed in the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation with such commitment that they devoted their lives to it—and in the case of Ridge, gave his life for it.

All these stories feature people whose lives help us frame larger conversation about what it means for the Nation to have survived repeated traumas. Popular portrayals, such as those focused on singular events like the Trail of Tears, don't want to get into the nuances, understandably, because the continued existence of Cherokee people and their sovereign governments defies stereotypes of disappearance. We emphasize that Cherokee resistance is ongoing, took many forms, and continues in Oklahoma, North Carolina, and other communities where Cherokee people live today. We challenge readers, especially non-Native ones, to see the connections between past events and modern-day manifestations of settler colonialism.

For this reason, we’ll also address common questions by providing context about current affairs, including criminal jurisdiction in Oklahoma and child welfare. Who has the right to raise Cherokee children? Whose laws apply to whom on Cherokee land? These questions really come down to the survival of a Native nation. Cherokees were debating how to best protect these sovereign rights in the 1800s, and they're still doing so now. We’re intentionally creating a narrative throughline that's legible to non-specialists and speaks to Cherokee people who know some of these stories but might think, "Oh yeah, I never thought of it that way. But now it makes sense how all these points are connected."

As an author writing for a broad audience, you must tell a clear story; but that doesn't mean you have to create binaries.

One of our hopes with this project is to muddy some waters. For example, there's an interesting scholarly debate about Indian slavery and whether the ways in which Native people began to adapt to plantation slavery in the decades before removal (the early 1800s) meant that they internalized Anglo-American society's views of race and racism. Historians, anthropologists and community scholars have written some great stuff. We aren't going to answer that question definitively, but we have the opportunity to describe this meaningful discussion for audiences who might not have access to it otherwise.

It's very easy to reduce human beings to stereotypes, which is to dehumanize them, especially the Native people who adapted to Anglo-American settlement in particular ways; this made them more acceptable to settler folks at the time, but perhaps less appealing to us with our modern sensibilities about what resistance should look like. One of the challenges of writing history, especially Native history, is fully humanizing a population that historically has been written about by everyone from missionaries to scholars in ways that reduce and minimize them to fit non-Native needs. Our goal is to create chapters about people who are neither always heroic nor doomed. Rather, by writing about places that are messy or contested, we can explore not just particular human experiences of the past but also explain the persistence of Cherokee ways of being today.

John Ross, full length portrait, facing front standing next to a small table. Ross was principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, 1828-1866. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

How do you confront gaps in the historical record?

We could not have written this project earlier in our careers even though we recognized the need for it; because while there are more primary sources on Cherokee than any other Native nation, they are deeply problematic in many ways.

For example, let’s consider the documents about the Trail of Tears, the removal records from the late 1820s through the 1830s—those records are dispersed among those of the Department of War and the Department of the Treasury. To say they are in chaos is a kind description. The National Archives is a Great Depression-Era invention. There was no organizational system in the 1830s. So basically, whatever ended up there a century later was kept in boxes in different places and was not filed in a particular way.

And so many of the records we are utilizing are a hodgepodge—take those referred to as “abandoned property records.” The properties weren’t abandoned: their owners were removed from their homes at gun point. But the surveyors came back in afterward and said, "Oh well, they left their livestock." Or other property. They didn't leave it willingly—they weren't allowed to take it. From those records, however, we can piece together extensive information about Cherokee economic development and social organization in the decades before removal. At the same time, those records are incomplete because many of them have been lost. We not only have had to read through volumes of records for every chapter of this book, but we’ve also had to identify where the gaps in the historical and documentary record exist. We recognize there are certain stories we have to get creative to tell, some that we just can't tell, and others that we can only speculate about.

Not understanding these gaps and why they exist could result in inaccurate conclusions. It's been the work of decades to get familiarized with what needs to be told, and how to tell that story. To continue with the removal era example, there are very, very few written accounts of the Trail of Tears by Cherokee people even though they were extremely literate at the time. People tell stories about it that survived in their families, but where are the written accounts from that generation?

The answer is that the Civil War resulted in the scorched earth destruction of the Cherokee Nation by Union, Confederate and guerilla forces. The tribal records that survived do so only because the then-Principal Chief loaded them up in a wagon and took them to Washington, D.C. Family letters, diaries, accounts that people would've written down didn't survive the Civil War—they were burned, left behind, or rained on in refugee camps. So, do we assume they never wrote about removal? No, not at all. We assume they did. But there really is a huge gap reflecting not only the loss and destruction of the removal era, but also the loss and destruction of the Civil War.

How did you approach the NEH grant?

My co-author and I wrote our first books on different topics. I wrote mine on federal Indian land policy, and she wrote hers on Cherokee social institutions—social welfare, asylums, orphanages and the Cherokee school system. We are both finishing our second books—mine about a particular Cherokee woman and hers about Cherokee education—and as we have worked on these independent projects, we each realized the next book needs to be this new history of the Cherokee Nation. After years of grumbling to one another that this book doesn’t exist, we realized that we are the ones to write it. Our strengths and our weaknesses complement each other, and we have different skill sets that we bring to the table to make this book comprehensive, accurate and creative.

The challenge was to explain this to the NEH, of course! There is nothing straightforward about writing an NEH grant, and it would be remiss to not thank Mary Muchane [Director of Sponsored Programs at Davidson College] and her staff for their support as well as staff at Penn State University, who provided feedback and assistance. When writing these proposals, one puts wishes into words. As we became more excited as we envisioned what this book could be, we remained humble because we recognize that this is just one of a massive number of brilliant projects evaluators have seen over the years.

We worked on this grant over years—literally. We had begun working on proposals for the NEH and trade presses back in 2019. We were ready to share them in 2022.

Our NEH proposal was accepted the first time we applied, and no one is more stunned than we are by this. This is not because we don't think the project is valuable; we have such a deep appreciation for how many of our colleagues doing impactful work have gotten rejected or were accepted after multiple attempts. We feel like unicorns.

Where do you start, and what are some of the challenges?

One of the challenges is time. Beginning in 2019, we started fleshing out the ideas of what this book would look like. During spring 2020, we began meeting regularly on Zoom and have continued to do so almost every week since then. We log on and write together. Having a collaborative writing process has been essential. The NEH grant buys us the time do this away from other professional obligations. We will be able to make progress much more quickly and efficiently with NEH support.

The NEH grant also covers our parallel processes of sharing drafts and collecting feedback from both Cherokee advisors and other historians, most of whom aren’t Cherokee. We've split this grant among time for drafting, getting feedback and making suggested revisions.

How did you decide to study history, and how did you decide on your areas of expertise?

I knew from when I was a tiny child that I wanted to be a history professor. My parents are history buffs, and our house was full of books. I was inspired by that love of books and reading and looking at pictures of the past. My father was particularly interested in the history of Illinois regiments in the Civil War. To this day, I'm proud that I've never been to Disney World, but I've been to most Civil War battlefields.

I thought as someone raised in the Chicago metro area that I would end up doing urban history and immigrant history because those were the stories I grew up hearing , and I thought they were fascinating. And then I went to the University of Illinois for my undergraduate degree, and that was at the point where Native students were raising awareness about the problematic mascot, Chief Illiniwek, who was a white student who would wear a Native costume and basically do a gymnastics routine at halftime. I participated in an alternative break trip to a Native community in Wisconsin and at that point, I realized that I didn't know anything about Native history. It was humbling to realize that I was not just ignorant, but profoundly miseducated. As a result of students agitating for it, I was lucky enough to take the first course in Native history the university offered. It was taught by one of the most outstanding historians of Native history, Fred Hoxie. I’ve been a student of Native history since, and I remain one even as I teach, research and write. I will never stop learning. There is so much more to learn.