Davidson College's Commitment to Education and Reconciliation

November 7, 2023

- Contact

- Mark Johnson

Davidson College announced today that it is advancing its work on understanding the college’s history regarding slavery and expanding its commitment to education and reconciliation efforts in the present and future.

Efforts to understand Davidson College’s historical ties to slavery have led to an expansion of the college’s education and reconciliation initiatives.

Davidson College announced today that it is advancing its work on understanding the college’s history regarding slavery and expanding its commitment to education and reconciliation efforts in the present and future.

The Board of Trustees and President Doug Hicks ’90 are establishing a new Committee on Education and Reconciliation to guide and support the college’s strategic efforts in understanding its history and building an inclusive Davidson College community.

The college released a new report on the history of Maxwell Chambers, whose gift in 1855 ensured the college’s survival during a financial crisis. The report was written, at the board’s request and without restrictions, by Dr. Hilary Green, the James B. Duke Professor of Africana Studies and Davidson’s public historian.

The report reveals not only that Chambers’ business practice of acquiring and selling plantations made him a trafficker of enslaved persons, but that Davidson College received at least five enslaved persons from Chambers and a factory in Salisbury. Further, the Trustees of Davidson College, long after Chambers’ death, sold that factory to representatives of the Confederacy.

The college will, among other steps, commission research and programming and establish permanent exhibits to convey the full history of Maxwell Chambers, a Salisbury money lender for whom the building is named and whose wealth largely was built off the institution of slavery. Davidson also will expand its efforts to identify, reach out to and build connections with descendants of those enslaved by Chambers and other founders and benefactors of the college.

These efforts connect with the research and educational programming of the Beaver Dam Plantation site, once the home of descendants of the college’s namesake, Revolutionary War Gen. William Davidson. The college is hiring for two positions, an archaeologist and a program manager, to support the archival and archaeological study of the enslaved persons who lived and labored there. On campus, design and construction are moving forward on “With These Hands,” a commemorative artwork by artist Hank Willis Thomas that will create a plaza on Davidson’s historic quad between four original campus buildings.

Hicks also announced that Davidson will initiate a summer program for local, underserved, high school-aged youth. Inspired by Davidson’s earlier program, Love of Learning, led and championed by the late Rev. Brenda H. Tapia, associate chaplain, the program will focus on college readiness.

The board’s actions, taken at their recent meeting on campus, follows three years of work by board members and college leadership and with input from the college community toward: understanding the college’s history, acknowledging the enslaved people who worked on campus and establishing policies governing the naming of buildings and public spaces. This work was guided by a trustees committee on acknowledgment and naming, led by Trustee Erwin Carter ’79.

Rendering of With These Hands—A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited

The Board also accepted the recommendation of the Acknowledgment and Naming Committee to leave the name of Chambers on that building.

“Maxwell Chambers’ history is the college’s history,” Hicks said in an interview. “The hard reality is that nearly every person associated with Davidson—presidents, trustees, professors, and benefactors—were implicated in the institution of slavery. Simply put, almost all of them were slaveholders. Every name in the college’s early history is associated with enslavement. Removing the name from this building would not expunge our history, and having the name remain requires us each day to account for it, to never forget.

“Our responsibility in the present is to talk about it, teach it and make sure it never happens again. We are called to educate our community about this history, and to expand the college outreach and reconciliation work toward descendants of those who were enslaved.”

Hicks, Board of Trustees Chair Alison Hall Mauzé ’84, Vice Chair Anthony Foxx ’93 and Acknowledgment and Naming Committee Chair Erwin Carter ’79 all co-signed a message to the college community today. The group wrote that “The Board accepted this recommendation to leave the Chambers name, driven by the moral conviction that the college’s collective energy should fuel actions for remembering the history, doing further research and teaching about it, and for reaching out to descendants of the enslaved in meaningful ways.”

Board and college leaders will support the creation of an extensive historical display to be developed for the campus community. Oak Row and Elm Row, two of the original campus buildings and located next to the “With These Hands” memorial, are expected to become historical and educational spaces.

The college plans to expand efforts toward identifying and engaging with the descendants of people enslaved by Chambers and by many of the original college leaders and faculty. Green, working off a request by the board, has spoken with descendants of people enslaved by Chambers who live in the Oberlin, Ohio, area. That’s where their ancestors migrated in 1855 and 1856. Chambers died in 1855, and his will bequeathed a quarter-million-dollar gift that enabled Davidson College to withstand the loss of many students and faculty before and during the Civil War.

Many of the persons he enslaved retained the name Chambers when they finally gained their freedom, and some of their descendants with whom Green spoke share that name today.

“Perhaps [the descendants’] most clear request,” Green wrote in a report to the board, “is that they be acknowledged, not erased.”

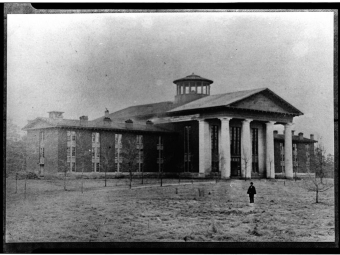

The old Chambers Building before the fire.

The Path to the Present

The Davidson College Commission on Race and Slavery was formed in 2017, with Foxx as chair. Their charge was to establish a framework by which the college could reach a better understanding of its own history, be accountable in the present and chart the future. The board and the college have completed a variety of actions in response to the commission’s 2020 report, including:

- Creating four tenured or tenure-track professorships in Africana Studies.

- Creating the role of the college’s public historian, now filled by Green.

- Anti-racism training across the college.

- A video history of Davidson College’s history with slavery, Jim Crow laws and segregation, produced exclusively to serve as part of a group conversation among first-year students piloted this year.

- Adjusting the salaries of the college’s lowest-paid employees to reflect a living wage.

The board, following the Race and Slavery Commission’s recommendations, also formed two special trustee committees. One focused on developing a permanent memorial to those whose labor was stolen or exploited on the campus.

The other committee was tasked with developing a policy for naming buildings and public spaces on campus and, in extraordinary cases, responding to requests for removing names. Committee members spent a year consuming research and hearing from historians and representatives of other institutions about naming practices. Committee members shared with members of the college community in 2021 what the committee had learned and the criteria they were considering for the naming policy.

After the policy was approved, the committee took up a request to rename the Chambers Building and asked Green to conduct research on Maxwell Chambers. Green is a nationally recognized expert on the often-unacknowledged history and legacy of slavery on university campuses and led the “Hallowed Grounds” project at the University of Alabama.

Inconsistent and Murky Story

Green spent months combing through records in the Davidson College and Oberlin College archives, as well as the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, among other sources. She consulted scholars and archivists and held Zoom conversations with 10 descendants of individuals enslaved by Chambers. Portions of Chambers’ life remain unclear, but Green delivered the most comprehensive account of the ties between Maxwell Chambers and Davidson College.

Her report outlines that Chambers’ life was full of inconsistencies and opaqueness. He was generous in charity but many times foreclosed on those who owed him money. He gave large sums to the Presbyterian Church but was not a member of any church. He freed 48 enslaved individuals, while alive and in his will, but he left more than 160 others enslaved, even bequeathing some individuals to relatives and friends.

“Chambers derived his wealth, power and reputation through his involvement in the institution of slavery and the slave trade,” Green’s report says. “He bought, sold and owned enslaved individuals. He accumulated his fortune off of the labor of enslaved people on plantations he owned through foreclosure and in a factory that he owned in Salisbury. His reliance upon slavery made possible his philanthropy to Davidson College and to the Presbyterian Church.”

Chambers connected with Davidson College through a Presbyterian minister whom he knew. When Chambers died, his will left money, land, stock and property worth approximately $250,000 to the college. The gift briefly made Davidson the wealthiest college in the South. Ultimately the college did not collect the full amount, in part due to litigation by Chambers family members, but Davidson was entangled in the will. A college trustee, D.A. Davis, served as executor. The college had received from Chambers a cotton factory in Salisbury at which, under the will’s conditions, five specific enslaved men were to be hired (provided a small level of wages) for two years, after which four were to be given their freedom. This made Davidson the de facto holder of enslaved individuals.

The college later sold the factory to the Confederate government, which used it as a prison that, in the last months of the war, was racked by disease that led to hundreds of deaths.

“These truths are awful and gut-wrenching for all of us,” said Alison Hall Mauzé, chair of the Board of Trustees. “The institution of slavery was a plague on this nation that left generation after generation of damage to families and an excruciating divide in our society. It is disturbing beyond description that the college was so deeply enmeshed in it, and it runs counter to our foundational commitments. Learning these details strengthens our resolve to do the hard work, to fulfill our responsibility to build a just and humane college community, and a better world.”

The community letter from Hicks and the three trustees said Green’s report is a testament to how far short of our values we can fall in hewing to the conventions of the day.

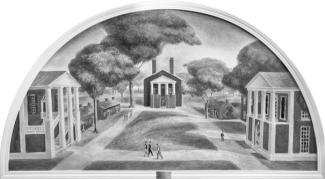

An oil painting by Kentucky muralist Frank Long showing the nineteenth-century design of Davidson College.

Thorough Examination

Trustees applied the college’s naming policy, which was approved by the Board last year, to what they learned about Chambers, examining a series of factors that could weigh for or against removing a name, such as:

- Does retaining the name interfere with the ability of college community members to teach, learn, work, and live in the community?

- Is the named feature reflective of the college’s history, or has it become part of the physical fabric of the student experience, such that there would be potential harm in removing the name?

- How central is the offensive conduct to the namesake’s life? Was it inextricable from their public life? Was it conventional at the time?

- Was the namesake’s relation to the college significant such that removing the name would raise concern about erasing the college’s history?

- Is there sufficient available documentary evidence of the offensive conduct?

- Was the name chosen for reasons unrelated to the offensive conduct?

- Can the college tell the full story if the name is removed?

Without Chambers’ gift, Davidson College likely would not have survived financial crises that struck in the 1850s, including a walkout that left the college without a student body. The first Chambers Building, constructed in 1860, burned in 1921. Its replacement, the current structure, was funded through insurance money and donations. The community drew so little connection to Maxwell Chambers at that time that, while he was noted at the groundbreaking, his name was not mentioned during the dedication ceremony in 1930. The new building’s full name is “The Chambers Building.”

Students over many decades associate the building not with an individual, but with its central role on campus and with their enduring recollections.

The board was motivated, in part, by Green’s conversations with many of the descendants of people enslaved by Maxwell Chambers whom she contacted, who emphasized that erasing the name of the building also erased theirs.

The trustees concluded, as Hicks and Trustee leaders wrote, that Chambers’ legacy was also Davidson College’s legacy. They emphasized that their top priorities are to educate the Davidson community on the college’s history with slavery, to publicly acknowledge that history, and to find connections with the community of those descended from people enslaved by founders and early benefactors of the college. Retaining the Chambers Building name serves as a daily reminder to the college of the importance of this work.

Trustees directed Davidson’s leadership to work toward those priorities.

For more information visit our FAQs.

What happens in understanding history, particularly history in the United States relative to slavery, is we’re confronted with the underbelly of who we were, where we were at a certain point in time. And the question, then, is: What is our responsibility to today? What is our responsibility to the future? What makes this question not so simple is that you can remove stuff—names, statues, whatever. And I can make an argument about why that is useful in some cases and maybe not useful in other cases. But what we don’t want to do, what we never want to do, is forget that history. Because that is the recipe to have it repeated.

Since the Commission on Race and Slavery’s report, faculty have developed programs, hosted speakers, designed courses and mentored student projects on these topics. Hicks and Trustee leaders announced that the college now will establish, from current and new sources, a $100,000 fund for research and teaching initiatives, “focused on the history of Davidson College and the ongoing inequality engendered by our nation’s history of enslavement, racism, and other forms of identity-based discrimination.”

The college’s other efforts toward accountability in the current day include building a curriculum that recognizes the wide range of backgrounds from which students arrive on campus and that cultivates humane instincts, creative and disciplined minds for lives of leadership and service.

As a Davidson community and as individuals in it, we continue learning about this history, and each of us will make different connections between the past and the present moment in which race and the legacy of slavery and segregation continue to be a source of division and injustice, Hicks and Trustee leaders wrote.

“We pledge to work with all constituencies and members of the college,” they wrote, “and with neighbors and descendants also directly affected by this history, in our continuing work to live, however imperfectly, Davidson’s highest ideals and aspirations.”

Update: On Oct. 23, 2025, hundreds of people gathered between buildings built from bricks bearing the thumbprints of enslaved laborers for a ceremony dedicating a new memorial in their honor. With These Hands: A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited serves as a place to remember and reflect upon those whose labor helped build the college and serve its students and faculty. Learn More.