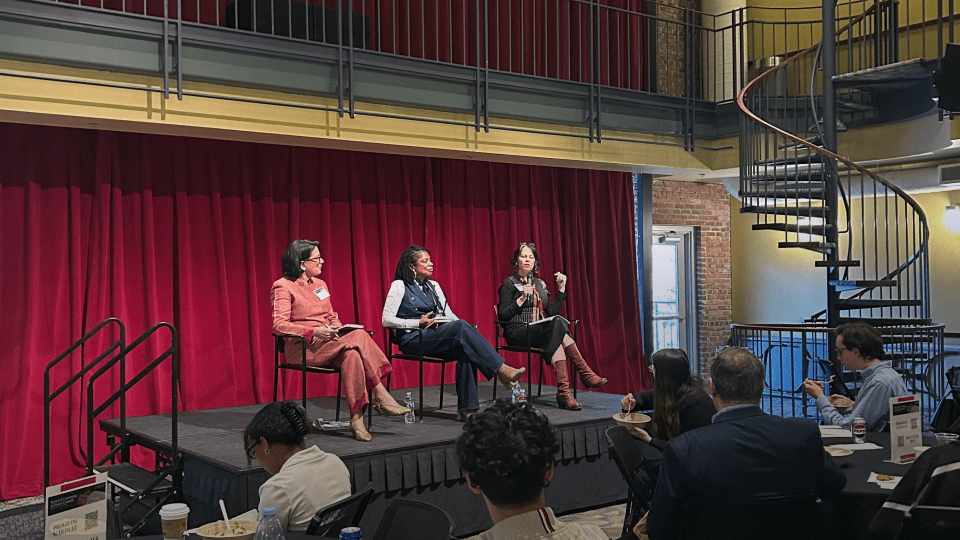

65 student honor council members and advisers from 18 colleges and universities gathered at Davidson College over the weekend for the second National Honor Council Conference.

Kenai is a 5-year-old Siberian Husky.

She lives in the mountains of western Virginia, and learning boundaries is part of her training — responding to commands or where she can go off the leash.

Once those limits are learned, though, she knows she is crossing them when she does. If she spots a deer, for example, it’s too tempting. She is off like a rocket. Afterward, some corrective discipline is administered, such as losing the freedom to be off-leash.

Kenai’s owner is J.T. Torres, Director of the Houston H. Harte Center for Teaching and Learning at Washington and Lee, an expert in educational psychology and a dog trainer. He drew on his experience in all of those arenas, including the concept of boundaries, in helping a group of students and advisers from college honor councils across the country last weekend. The group was figuring out, among other challenges, how they model and adjudicate ethics in the era of artificial intelligence.

“We need to reframe the idea that students are trying to cheat,” Torres said in a pre-conference interview, “and think more about how students are trying to survive college.”

More than 60 student honor council members and advisers from 18 colleges and universities gathered on Davidson College’s campus over the weekend for the second National Honor Council Conference. Convening is made possible through the support of a grant from the Wake Forest University's Educating Character Initiative.

The honor council representatives traveled from as far as Minnesota’s St. Olaf College and Amherst College, in Massachusetts. Their roles vary, depending on the institution, but two primary functions thread through all of them: providing leadership in ethical conduct and deciding cases of alleged cheating and other honor code violations.

Institutions that have honor councils rely on them to help strengthen an already high level of trust within the community, where they may take unsupervised exams or leave a backpack in a public space with little fear of theft. Davidson organized and played host to the inaugural National Honor Council Conference last year. The events reflect the college’s emphasis on its role as a public good, including the cultivation of ethics, honor and leadership — one of the program areas within Davidson’s new Institute for Public Good.

AI’s ability to perform tasks previously limited to humans, such as writing a research paper, has pushed honor councils into untrod territory. Michael Pyo, a senior at Pennsylvania’s Haverford College who attended the conference, is leading a committee that is writing a new AI section to the college’s honor code.

“We’re trying to shape and mold the honor code,” he said, “to adapt to modern times.”

Bowdoin College is organizing similar pathfinding discussions, said Lillian Regal, a sophomore at the college in Maine who traveled to the conference.

“What kind of behavior should we be passing judgment on?” she said. “Is AI plagiarism?”

Torres said that humans have instinctive reactions to new ideas or cultural shifts, and the knee-jerk response to AI is to lock it down in order to prevent cheating — craft tough policies on its use and penalties for misuse.

College, though, is intended as a venue and time for students to safely make mistakes and learn from them. Students should be able to experiment with and use AI appropriately in order to learn how to navigate it ethically, Torres said. For that to happen, colleges and universities need to create and strengthen the motivations for ethical use of AI and create a learning environment that reduces the temptation to have a bot write a paper.

Torres told the group that humans will take the easier path to complete a task, whether it’s a class assignment or exercising. That’s where the Ikea effect comes in, he said. Research shows people ascribe a higher value to something when it requires harder work. They value an Ikea chair, which they struggled to assemble, more than professionally assembled furniture. Justifying the effort and feeling ownership increase the value.

AI presents an easier path in which thinking is optional, Torres said. Colleges must create the atmosphere where the value of human thinking is clear, where a student is disappointed when they don’t feel ownership, when they are not reflected, as a person, in a paper or project.

“You want them concluding: ‘It’s not just honor to a code. I need to be an ethical person,’” he said. “It’s more honor to yourself. Having the honor to do the work that we need to do, that makes us proud.”

Honor council members described quests for clarity around AI. A professor could clarify the goal of an assignment is writing, so asking ChatGPT to write it is cheating. But if the goal is analyzing a problem and communicating it is secondary, help from AI may be permissible.

“A lot of it is what’s the point of the assignment,” said Yeseo Lim, a sophomore at Bryn Mawr College, in Pennsylvania.

Another large piece of the AI temptation is helping students with time management, Torres said. Students wrestle with a heavy workload in a high stress, high engagement environment. They get a ton of assignments and seek the fastest way to check tasks off the list. AI makes that easier. Students rationalize it as getting a requirement done, rather than cheating.

“They’re doing a lot,” Torres said. “They might be making decisions to use available tools to stay above water.”

He encouraged classes to focus more on depth than breadth — fewer assignments that are larger and more engaging, work with which students feel more invested. “Don’t cheat” might equate to “don’t walk on the grass,” while the student sees “don’t be a cheater” as cautioning against an identity that they don’t want.

“The more they think of it as busy work,” he said, “the more tempting it is to use AI.”

It’s the students’ version of the deer.

The ability to make an error and try again helps students figure out thresholds of what they can do on their own, Torres said. And if students complete work that requires more effort, he said, they put a higher importance on it and react more strongly to the idea of crossing a line.

In other words, it’s about boundaries.