‘With Their Hands, This Place Was Made’: Davidson College Dedicates Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited

October 24, 2025

- Author

- Mary Elizabeth DeAngelis

In her 60 years at Davidson College, Lula Bell Houston washed students’ clothes, sheets and towels, carefully setting aside the money, pens and keys she’d find in their pockets to return to them with their clean laundry.

Fred Deese mowed lawns, planted trees and trimmed hedges as a groundskeeper. As a janitor, he mopped, vacuumed, washed windows and emptied trash cans. His wife, Janie, served as a maid to presidents and professors, carefully dusting family mementos and preparing guest rooms.

They’re among the many Black workers, unknown and known, whose contributions went unacknowledged across the college’s history, from enslavement during the college’s 1837 founding through Jim Crow laws that prohibited them from voting or owning property and kept their wages low.

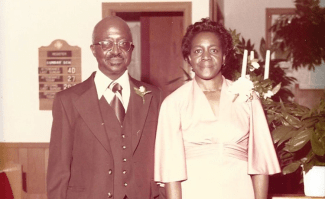

Lula Bell Houston

Fred and Janie Deese

On Thursday, hundreds of people gathered between buildings built from bricks bearing the thumbprints of enslaved laborers for a ceremony dedicating a new memorial in their honor. With These Hands: A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited serves as a place to remember and reflect upon those whose labor helped build the college and serve its students and faculty.

Hank Willis Thomas at the dedication ceremony

Renowned artist Hank Willis Thomas designed the large bronze sculpture of two work-worn hands in collaboration with the architectural firm Perkins&Will. It sits prominently near the original Oak and Elm Row buildings just off Main Street, two of the original six buildings still standing.

A beautiful fall afternoon sun cast a glow on the sculpture. Visitors from Davidson’s west side to the West Coast mingled for an occasion that was both solemn and celebratory. They hugged family members, friends and former coworkers as well as students, faculty and staff. They paused for photographs, prayed and remembered.

“My parents would be so pleased,” said Willie Deese, a son of longtime college workers Fred and Janie Deese. “They took great pride in doing whatever they did with excellence. They’d feel good that their hard work was being recognized and appreciated, particularly by today’s generation.”

Thomas was among the speakers at the ceremony and highlighted an artist’s talk Thursday night. Best-selling author and poet Clint Smith, a 2010 alumnus of Davidson, delivered the college’s annual Reynolds Lecture Wednesday night, and, on Thursday, recited the poem he wrote for the dedication.

Listen to author Clint Smith read the poem:

Ruby Houston, a retired educator, administrator and community leader, said she felt a sense of awe when she first saw the monument, and felt the weight of what it represents.

“People were mistreated, they were paid unfairly; it’s been a lot,” she said. Her many family members who worked at the college include her now 100-year-old mother, Bernice. “It gives me hope that we’re finally acknowledging what our reality was during those times.”

Davidson is adding to its history. The college is recognizing those who helped build the campus — a central role in its founding — who were left out of that history, bringing these community members from across the centuries into its narrative timeline, President Doug Hicks ’90 said.

“These reverential hands face skyward, calling us to live by the better angels of our nature,” Hicks said. “May we open our own hands and our hearts today to honor the whole people of Davidson College.”

Family Reflections

Dr. Shannon Coleman, granddaughter of Fred and Janie Deese, says their belief in the power of education lives on through the generations. She dedicated her doctoral thesis to them.

Loria Houston, daughter of longtime laundry worker, and namesake of Lula Bell’s Resource Center, Lula Bell Houston, reflects on the dedication of With These Hands: A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited, and what it would mean to her mother.

Willie Deese reflects on his parents' dreams for their children and how, through education, those dreams have been realized. Deese, a retired Merck & Co., executive and his siblings have built their lives on the firm foundation provided by their parents, Fred and Janie Deese.

Educator and community leader Ruby Houston experienced a hopeful, spiritual moment when she first saw With These Hands: A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited on Davidson College’s campus.

Apology, Acknowledgment

Like Davidson, many institutions across the United States have examined their history of slavery and the persistence of racial discrimination during the Reconstruction, Jim Crow and segregation eras. In 2020, then-President Carol Quillen publicly apologized for the college’s past actions after the extensive research of Davidson’s Commission on Race and Slavery. The commission’s recommendations included a memorial.

The college has aimed to build on what is learned of the past to guide the path forward. Davidson has hired new professors, expanded courses and community programs and launched student and faculty research. It’s transforming the nearby Beaver Dam farmhouse where enslaved people once labored into a research and learning laboratory that will eventually open to the public.

Students, professors and archivists continue to pore over public records, letters, diaries, college ledgers and year books, visit cemeteries, and talk to families to learn more about the lives of the enslaved and exploited workers.

“By putting the memorial where enslaved people labored, we are also recognizing the grounds that they helped shape, and the landscapes they maintained during and after slavery,” said Hilary Green, James B. Duke Professor of Africana Studies, who specializes in African American history, the Civil War and Reconstruction. “We must acknowledge that legacy honestly and truthfully and listen to the voices of people who came before us and who were far too long excluded.”

Commemoration is an apology, Green said. The acknowledgment of wrongdoing is a critical step toward building a better present and future.

“If we don’t have honest conversations about the entire experience for everyone here, including this history of African American workers,” she said, “we won’t be able to move forward as one Davidson College community.”

The memorial to the enslaved and exploited on the Davidson College campus is located on the oldest part of campus, close to Main St. and accessible to the citizens of Davidson whose ancestors may have labored at the college, says Malcolm Davis of architectural firm Perkins&Will.

Hilary Green addresses the crowd at the dedication ceremony

Many formerly enslaved people with few options continued working at Davidson after slavery ended, and their families’ lives remained intertwined with the college.

Castella Conner’s family counts more than 250 years of service to Davidson over four generations. They touched every corner of campus, from painting dorm rooms and classrooms to repairing failing equipment and keeping flowers blooming.

Among those attending the dedication was Robert Adair, a New Jersey physician and descendent of enslaved workers who helped build the college. His mother, the late Thelma Davidson Adair, became the college’s first Black trustee in 1983.

“She cherished her relationship with Davidson College,” Robert Adair, 82, said in a recent interview. “She was exceedingly proud of her Davidson heritage and the way both sides, (Black and white) of that family came together. She was proud of Davidson and where it was going.”

Thelma Davidson Adair

Keeping Presidents’ Households Running

Bernice Torrence Houston helped keep the households of college presidents running, dispensing wisdom as she cooked, cleaned, grocery shopped and shuttled visitors to the airport.

She spent her later years in that role as the housekeeper for John Kuykendall ’59, who served from 1984 to 1997.

“I never had a problem with any of them,” she said of the presidents. “The Kuykendall family was like family to me — they still are to this day.”

Discrimination, though, overshadowed much of her life in the segregated south, barred her from stores and restaurants, subjected her to racial slurs and belittlement by strangers.

“Things have changed so much in my lifetime,” she said. “Davidson has made so many great changes. When I first started working there, white people didn’t associate with Black people. You worked and you went home. With the Kuykendalls, I felt free to go anywhere in the college, which I hadn’t before.”

The Kuykendalls visit her often and were among more than 260 guests at a party celebrating her 100th birthday at Davidson Presbyterian Church in September. She attended Thursday’s ceremony with her daughters and glowed with joy as her many friends stopped to greet and hug her.

Bernice Torrence Houston with former President John Kuykendall and his wife, Missy

The Kuykendalls with Mitzi Short '83

“It means a lot,” she said of the memorial. “There are still a lot of problems in the world. You’ll always have those ‘antiques’ who don’t like how far we’ve come, but I feel like this is a good step.”

Striving for Better Days

Delores Deese Black grew up with Davidson as a constant presence in her family’s life. Her parents worked long hours at the college. After work and on weekends, Fred Deese ran a landscaping business with his sons. Janie took on housekeeping jobs in town.

They lived on a farm, which helped feed them and bring in extra income. On Sundays the family woke up early for another side job — cleaning churches— then headed home to change and attend their own service. As a teenager, Black babysat for faculty members’ children.

She remembers her father talking about a pivotal moment as a young man, when he didn’t get a postal carrier job because he didn’t have a high school diploma.

“If these kids want to do better than I’ve done,” Fred Deese told his wife, “I will do anything I can to make that possible.”

And he did.

All of their children, except for a daughter with Down Syndrome, went to college and led successful careers in business, social work, education and public health. Four earned graduate degrees.

Last year, Black’s daughter, Shannon Coleman, dedicated her doctoral dissertation to her grandparents.

“They placed the value and importance of obtaining an education on my mother and her siblings,” she wrote. “Continuing the legacy of living out their hopes and dreams is my deepest honor.”

Black, 72, couldn’t make the ceremony, but Coleman and Willie Deese were there to represent their family. They all feel a deep connection to what the memorial represents.

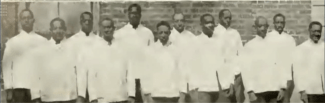

Fred Deese and his father Willie with other Jim Crow and post-desegregation employees

Fred Deese

Their mother, Janie, owned a single, sack cloth dress as a child.

Black was one of the first African American students to integrate her public high school, where she often felt threatened by white students who didn’t want her there.

Her Davidson College memories are fonder, from the families for whom she babysat to riding along in her dad’s truck to pick up food waste for their farm animals. She says her parents had friendly relationships with students, faculty and coworkers, especially in later years.

Fred Deese died in 1993, and Janie, in 2021.

“Mom lived to see more progress, I think Dad would be happy to know that a lot of his dreams have come true,” Black said. “If they could be here, and see the memorial, they’d be smiling.”

250 Years of Family Service

Castella Conner, who retired from the college’s admission and financial aid office as applications processing manager in 2022, spoke at the ceremony on behalf of the local community.

Castella Conner speaks at the dedication ceremony

Her father, Talmadge Conner Sr., retired from his 40-years at Davidson as a custodial supervisor. Her mother, Cecelia Simolton Conner’s many jobs included cooking for students in an eating house, helping care for President Walter Lingle’s ailing wife in the 1930s, and working in the laundry room.

Castella’s brother, Talmadge Conner Jr., spent 21 years in Building Services, moving furniture, mopping and waxing floors and tending the grounds before retiring in 2019. Other family workers included her late brother Charlie, grandfather Calvin Simolton, aunts, uncles and great-grandparents.

“Today marks a significant chapter in our shared history,” Castella Conner told the crowd gathered on the land where her family once toiled. “Even as books may face censorship, the truth of our past cannot be erased from our memory.”

Commemoration is especially important for families of those who are no longer living. She said she prays that the memorial marks a further commitment from the college and community toward building a better future.

She quoted Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.:

“Forgiveness does not mean ignoring what has been done or putting a false label on an evil act. It means rather that the evil act no longer remains a barrier to the relationship.”

In an earlier conversation, she described her feelings upon seeing the hands for the first time.

“The hands are beautiful,” she said. “As I walked on the grounds it was an unexpected emotion. I felt the spirit of my forefathers and foremothers. I felt their pain, determination and love for their families, and for the college.”

Tending the Laundry

As a little girl and the youngest of four children, Loria Houston would go to work with her mom, Lula Bell, when she didn’t have a family member or friend available to babysit.

Lula Bell Houston woke up at 4:15 a.m., cooked her family breakfast, then headed to the college’s laundry room to start work at 6 a.m. On Saturdays, she cleaned and did laundry at local homes.

It was a hard life, yet many friendships formed and deepened at the college. Lula Bell Houston and laundry room coworkers often sang as they washed, dried, ironed and folded. They called themselves “The Launderettes.”

Davidson College Laundry Staff, 1988

“Everyone she worked with in that laundry room was like family,” Loria Houston said. “They all treated me like a daughter. And whenever we’d go into town and see professors or students, they would come up to my mom and tell her how much they loved her.”

Her legacy lives in the Lula Bell's Resource Center, a campus resource that offers students help with professional clothing for job interviews, food, kitchen supplies and textbooks, as well as financial literacy skills.

Lula Bell Houston died in 2017 at 94. Loria Houston said she felt her mother’s presence at the ceremony as she gathered with her family and community and performed the spiritual, There Is a Balm in Gilead: “There is a balm in Gilead, to make the wounded whole. There is a balm in Gilead to heal the sin-sick soul.”

On Thursday she wore a silver charm bracelet with her mom’s picture on it.

“I’m so glad to have this memorial; they deserve to be remembered,” Houston said. “Those Black hands labored, washed clothes, cleaned, fed students and helped Davidson College become so successful.”

She recently visited the memorial to prepare for the ceremony.

“When I saw those hands, something went through me,” she said. “It was peace.”

Event Gallery

Full Recording: Davidson College Dedicates Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited

Hundreds of people gathered on the Davidson College campus between buildings built from bricks bearing the thumbprints of enslaved laborers for an October ceremony dedicating a new memorial in their honor. With These Hands: A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited serves as a place to remember and reflect upon those whose labor helped build the college and serve its students and faculty.